Reset Filters

Articles

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

Can the Florida Insurance Market Withstand a US$100 Billion Repeat of Hurricane Andrew?

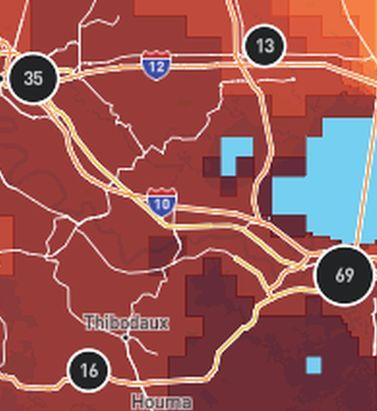

Hurricane Andrew’s landfall in Florida in 1992 changed the face of property catastrophe insurance and kick-started many new initiatives, including the development of hurricane risk modeling. However, with significant exposure growth, the impact of social inflation, and climate change complications, the insurance market could struggle to respond to a repeat of Andrew. The wide-ranging impact of Hurricane Andrew on the Florida insurance market is a familiar story within the risk management world. However, 30 years on from August 24, 1992, when Andrew made landfall in Dade County, Florida, memories appear to be getting shorter, as the insurance industry once more seems to be in danger of underestimating its exposure to a Category 5 storm hitting the state. Image from the GOES-7 satellite shows Hurricane Andrew at its peak intensity on August 23, 1992, before making landfall near Homestead, Florida. Image source: NOAAWhen Hurricane Andrew came ashore as the first named tropical storm of the 1992 North Atlantic hurricane season, it followed a seven-year hiatus in major hurricane activity in Florida. Industry predictions at the time were that it would cost insurers around US$4 billion to US$5 billion, but Andrew ended up costing the insurance industry US$15 billion (in 1992 values) for Florida claims, and it caused the deaths of 44 people in the state. Following Hurricane Andrew, more than 650,000 claims were filed, leaving eight insurers becoming insolvent and a further three driven into insolvency the following year. Fast forward to today, and RMS® predictions for a repeat of Andrew would see the insured loss for wind and surge in the range of US$80 billion (GR) and US$90 billion (GU), in which other non-modeled losses and social inflation could lead to a US$100 billion event. Aftermath of Andrew The losses from Hurricane Andrew vindicated the need for catastrophe modeling solutions including the use of multiple simulated storms beyond those previously experienced in history. Catastrophe models enabled the new Bermuda reinsurance market: eight new reinsurers were established without the need for their own historical experience. In time, catastrophe models would enable the creation of insurance-linked securities such as catastrophe bonds, to tap into capital markets for alternatives to reinsurance. Without Hurricane Andrew, it might have taken much longer for this revolution to happen. The crisis caused by Andrew certainly precipitated some rapid and innovative changes to help manage a much larger hurricane risk cost than previously recognized, allowing the market to prepare for the hyperactive Florida hurricane seasons of 2004 and 2005. However, the following years were unusually quiet for intense storms landfalling in Florida, encouraging actions that further raised insurers’ hurricane risk costs. Among these was the 25 percent roof replacement rule in 2007, which mandated that if 25 percent or more of a roof is ‘repaired, replaced or recovered’ in any 12-month period, then the entire roofing system or roof section must be brought up to the latest building code. “Until the hurricanes returned with a vengeance in 2017,” says Peter Datin, senior director of modeling at RMS, “the significant additional cost imposed on insurers due to this code update was not clear.” Development of Hurricane Modeling Before Hurricane Andrew, exposure mapping by the insurance industry involved tracking premiums at a fairly coarse ‘Cresta Zone’ resolution. Post-Andrew, as modelers provided insurers with the ability to model exposures at a finer scale, insurers recognized how higher resolution data could provide a more accurate assessment of risk. RMS released its first hurricane model in 1993. Since then, there have been many updates and innovations, from basin-wide stochastic tracks, coupled ocean-atmosphere storm surge modeling, and significant enhancements in damage assessment modeling. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Robert Muir-Wood, chief research officer at RMS, coined the term ‘post-event loss amplification’ (PLA) to cover all processes that can raise losses after a major catastrophe, such as demand surge and claims inflation. Auguste Boissonnade, vice president of model development at RMS, who designed the first RMS hurricane model, worked on how to quantify these different factors in generating the overall insurance loss after cat events. Hurricane Katrina floodingFor the most extreme catastrophes, when damage requires the long-term evacuation of large parts of a city, the definition of a “super catastrophe” (or “super-cat”) event applies, where secondary consequences can be a significant component of the original damage. The flooding of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina was such a super-cat. “With the hurricane catastrophes of 2004 and 2005 came the realization that cat loss models needed to allow for undervaluation of insured exposures as well as the secondary impact of economic, social, and political factors that could amplify the losses,” Boissonnade says. After major hurricanes, RMS vulnerability modelers review lessons that can be learned from the events and the resulting claims data. “Through claims analyses, it has been possible to quantify the degree to which changes in wind design codes have reduced damage and losses to buildings and incorporate those learnings into cat models,” added Datin. Current Market Dynamics The average cost of an annual homeowner’s policy in Florida is expected to soar to US$4,231 this year, almost three times the U.S. annual average, according to the Insurance Information Institute. Five Florida market insurers have already gone insolvent so far in 2022, faced with rising claims costs and increased costs for reinsurance. Meanwhile, the number of policies written by Citizens, a post-Andrew creation, has risen to over a million, as insurers have either gone insolvent, withdrawn capacity from the market, or had their ratings downgraded, making it harder for insureds to secure coverage that will meet their mortgage lenders’ approval. In July 2022, rating agency Demotech wrote to 17 insurers warning them they could be downgraded from A (exceptional) to S (substantial) or M (moderate), potentially impacting millions of policyholders whose mortgage providers demand home insurance from the strongest-rated carriers. Florida legislators then looked to circumvent the use of Demotech ratings with a new stopgap measure, where Citizens take on a reinsurance role to pay claims for insolvent insurers. At the same time, insurers are struggling to secure reinsurance capacity, and Citizens only managed to get a third of its desired reinsurance cover, making it harder for carriers to deploy sufficient capacity to meet the demand for hurricane coverage. There has also been a huge increase in the volume of catastrophe claims in recent years, driven by social inflation and undervaluation of exposures. Likely Impact of Andrew Now “Our prediction that a repeat of Andrew today could cause as much as US$100 billion in insured losses is based in large part on changes in exposure and population since 1992, coupled with updated predictions of the impact of wind and storm surge, with significant anticipated post-event loss amplification. Together these components reveal a more complete picture of potential economic and insured losses,” says Mohsen Rahnama, chief risk modeling officer at RMS. Combined wind and surge losses for a repeat of Hurricane Andrew are estimated at US$87 billion. Post-event loss amplification, whether it is from a slow recovery, supply chain issues from COVID-19, or current inflationary trends, could take the ultimate loss closer to US$100 billion. The impact of storm surge, particularly with the climate change-related rise in sea levels, is also more pronounced now compared to estimates at the time of Andrew. South Florida property developmentAdded to this is the significant demographic shift in Florida. As of this year, the population of Florida is estimated at over 22 million – a 61 percent increase from the number of people in 1992. Building counts in Andrew’s wind and surge footprints have increased by 40 percent to 1.9 million and by 32 percent to 55,000 respectively. Economic exposure has also increased by 77 percent in the wind footprint and 67 percent in the surge footprint. And in Miami-Dade County, the number of high-rise buildings that are over 15 stories has tripled since 1992, many of which are now potentially in Andrew’s surge footprint. “While the wind was the main driver of loss in 1992, the number of new, high-valued buildings near the coast suggests that storm surge losses may play an increasing role in a repeat of this event,” says Rahnama. In constant-dollar terms, economic exposure has grown substantially within both Andrew’s wind and surge footprints, based on an analysis of the total built floor area (see Figure 1). On top of this, cost inflation since 1992 has been substantial, with replacement costs in Florida estimated to have increased between two times and 2.5 times since 1992, based on historical construction cost indices. Figure 1: Exposure growth in Hurricane Andrew’s footprint (in constant dollars). Source: RMSOne key uncertainty in estimating the losses from a repeat of Hurricane Andrew concerns the impact of claims litigation. “Irma in 2017 was the first significant hurricane to make landfall since the 25 percent roof replacement rule was expanded in 2017 to all buildings across Florida, and it contributed to a significant increase in claims frequency and severity, as roof damage sustained during the storm attracted many roofing contractors, who handed over their exaggerated claims to be pursued by attorneys,” recalls Datin. An estimated US$15 billion has been paid to claimants by insurers in Florida since 2013, driven by assignment of benefits (AOB) cases, where litigation has capitalized on the 25 percent roof replacement rule, with a significant portion of the cost being driven by attorney’s fees on both sides. However, a new law passed by the Florida legislature in May 2022 changed the 25 percent roof replacement rule to exempt roofs “built, repaired, or replaced in compliance with the 2007 Florida Building Code, or any subsequent editions of the Florida Building Code.” “This means that only the damaged portion of the roof on newly built or upgraded roofs needs to be repaired after a damaging wind event instead of the entire roof or roofing system. Most importantly for insurers, the right of the contractor or assignee to obtain compensation for attorney fees – that drives up the cost of claims even further – has been removed,” adds Datin. Muir-Wood adds: “There is further hope for insurers following a recent appeal court ruling in Florida which could provide the blueprint for insurers to successfully argue against contractors in such lawsuits. Here we have at least one factor that is now being brought under control, which has significantly raised the insurance costs of hurricane losses. However, insurers will be watching closely to see if there is any reduction in social inflation because of recent legislative measures.” Can the US$100 Billion Repeat of Andrew be Prevented? Should another Category 5 hurricane make landfall in southeast Florida today, not only will the insured loss be more considerable, but the insurance industry will face major challenges that could severely impact its ability to withstand the event. What can the risk management industry do to mitigate losses? Risk modeling has advanced dramatically. “Insurers need to collect detailed data on their exposures and values and then employ high-resolution modeling alongside all those factors that can affect the ultimate loss, whether from post-event loss amplification or from more resilient construction standards,” says Muir-Wood. The spirit of the industry working together with regulators, similar to post-Andrew, needs to be resurrected. “To help insurance carriers to remain competitive, regulators and legislators have been working with the industry to prevent claims litigation from getting out of control and potentially threatening the viability of hurricane insurance in Florida,” adds Boissonnade. “And legislators also need to keep a close eye on how claims respond to the changes to the 25 percent roof replacement rule, and in measures that reduce the need for litigation, so as to reduce vexatious claims,” he adds. Datin acknowledges the role that risk modelers can play, “The catastrophe modeling community has already helped drive positive change in Florida by demonstrating the impacts of building codes and the effects of AOB-driven claims inflation on modeled risk.” In addition, says Rahnama: “It’s crucial that modeling for hurricane risk takes greater account of the effects of climate change on global warming and sea level rise, and the impact those will ultimately on wind and storm surge in the event of another hurricane like Andrew. Let’s not sleepwalk into another Andrew-type scenario. The insights are there, and the warning signs have flashed – we just need to learn from history.”

RMS HWind Hurricane Forecasting and Response and ExposureIQ: Exposure Management Without the Grind

Accessing data in real-time to assess and manage an insurance carrier’s potential liabilities from a loss event remains the holy grail for exposure management teams and is high on a business’ overall wish list A 2021 PwC Pulse Survey of U.S. risk management leaders found that risk executives are increasingly taking advantage of “tech solutions for real-time and automated processes, including dynamic risk monitoring (30 percent), new risk management tech solutions (25 percent), data analytics (24 percent) [and] integrated risk management tools on a single platform (19 percent)”. PwC suggested that as part of an organization’s wider digital and business transformation process, risk management teams should therefore: “use technologies that work together, draw on common data sources, build enterprise-wide analytics and define common sets of metrics.” Separately, Deloitte’s 2021 third-party risk management (TPRM) survey found that 53 percent of respondents across a range of industry sectors wanted to improve real-time information, risk metrics, and reporting in their organizations. With the pandemic providing the unlikely backdrop for driving innovation across the business world, the Deloitte survey explained the statistic with the suggestion that one impact of COVID-19 “has been a greater need for real-time continuous assessment and alerts, rather than traditional point-in-time third-party assessment.” Event Forecasting and Response with HWind and ExposureIQ Natural catastrophe events are a risk analytics flash point. And while growing board-level awareness of the importance of real-time reporting might seem like a positive, without marrying the data with the right tools to gather and process that data, together with a more integrated approach to risk management and modeling functions, the pain points for exposure managers on the event frontline, are unlikely to be relieved. RMS® ExposureIQ™ is an exposure management application available on the cloud-native RMS Intelligent Risk Platform™, which enables clients to centralize exposure data, process it, write direct reports and then run deterministic scenarios to quickly and accurately assess their exposure. When an event is threatening or impacts risks, an exposure management team needs to rapidly process the available data to work out their overall exposure and the likely effect on insured assets. The integration of event response data such as HWind into the ExposureIQ application is where the acquisition of this hazard data really starts to make a difference. The 2022 North Atlantic hurricane season, for example, is upon us, and access to regular, real-time data is relied upon as a crucial part of event response to tropical cyclones. With reliable event response analytics, updated in real-time, businesses can get fully prepared and ensure solvency through additional reinsurance cover, more accurately reserve funds, and confidently communicate risk to all stakeholders. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Hurricane Center (NHC) has long been viewed as a valuable resource for forecasts on the expected track and severity of hurricanes. However, according to Callum Higgins, product manager, global climate, at RMS, “There are some limitations with what you get [from the NHC]. Forecasts lack detailed insights into the spatial variability of hazard severity and while uncertainty is accounted for, this is based on historical data rather than the forecast uncertainty specific to the storm. Hurricane Henri in 2021 was a good example of this. While the ultimate landfall location fell outside the NHC ‘cone of uncertainty’ four days in advance of landfall, given the large model uncertainty in the track for Henri, HWind forecasts were able to account for this possibility.” Introducing HWind RMS HWind provides observation-based tropical cyclone data for both real-time and historical events and was originally developed as a data service for the NHC by renowned meteorologist Dr. Mark Powell. It combines the widest set of observations for a particular storm in order to create the most accurate representation of its wind field. Since RMS acquired HWind in 2015, it has continually evolved as a solution that can be leveraged more easily by insurers to benefit individual use cases. HWind provides snapshots (instantaneous views of the storm’s wind field) and cumulative footprints (past swaths of the maximum wind speeds) every six hours. In addition, RMS delivers hurricane forecast data that includes a series of forecast scenarios of both the wind and surge hazard, enabling users to understand the potential severity of the event up to five days in advance of landfall. “Because HWind real-time products are released up to every six hours, you can adapt your response as forecasts shift. After an event has struck you very quickly get a good view of which areas have been impacted and to what level of severity,” explains Higgins. The level of detail is another key differentiator. In contrast to the NHC forecasts, which do not include a detailed wind field, HWind provides much more data granularity, with forecast wind and surge scenarios developed by leveraging the RMS North Atlantic Hurricane Models. Snapshots and cumulative footprints, meanwhile, represent the wind field on a 1x1 kilometer grid. And while the NHC does provide uncertainty metrics in its forecasts, such as the “cone of uncertainty” around where the center of the storm will track, these are typically based on historical statistics. “HWind accounts for the actual level of model convergence for a particular storm. That provides you with the insights you need to make decisions around how much confidence to place in each forecast, including whether a more conservative approach is required in cases of heightened uncertainty,” Higgins explains. HWind’s observational approach and access to more than 30 data sources, some of which are exclusive to RMS, means users are better able to capture a particular wind field and apply that data across a wide variety of use cases. Some HWind clients – most notably, Swiss Re – also use it as a trigger for parametric insurance policies. “That’s a critical component for some of our clients,” says Higgins. “For a parametric trigger, you want to make sure you have as accurate as possible a view of the wind speed experienced at underwritten locations when a hurricane strikes.” Real-time data is only one part of the picture. The HWind Enhanced Archive is a catalog of data – including high-resolution images, snapshots, and footprints from historical hurricanes extending back almost 30 years that can be used to validate historical claims and loss experience. “When we're creating forecasts in real-time, we only have the information of what has come before [in that particular storm],” says Higgins. “With the archive, we can take advantage of the data that comes in after we produce the snapshots and use all of that to produce an enhanced archive to improve what we do in real-time.” Taking the Stress out of Event Response “Event response is quite a stressful time for the insurance industry, because they've got to make business decisions based around what their losses could be,” Higgins adds. “At the time of these live events, there's always increased scrutiny around their exposure and reporting.” HWind has plugged the gap in the market for a tool that can provide earlier, more frequent, and more detailed insights into the potential impact of a hurricane before, during, and following landfall. “The key reason for having HWind available with ExposureIQ is to have it all in one place,” explains Higgins. “There are many different sources of information out there, and during a live event the last thing you want to do is be scrambling across websites trying to see who's released what and then pull it across to your environment, so you can overlay it on your live portfolio of risks. As soon as we release the accumulation footprints, they are uploaded directly into the application, making it faster and more convenient for users to generate an understanding of potential loss for their specific portfolios." RMS applications such as ExposureIQ, and the modeling application Risk Modeler™, all use the same cloud-native Intelligent Risk Platform. This allows for a continuous workflow, allowing users to generate both accumulation analytics as well as modeled losses from the same set of exposure data. During an event, for example, with the seven hurricane scenarios that form part of the HWind data flow, the detailed wind fields and tracks (see Figure below) and the storm surge footprints for each scenario can be viewed on the ExposureIQ application for clients to run accumulations against. The application has a robust integrated mapping service that allows users to view their losses and hot spots on a map, and it also includes the functionality to switch to see the same data distributed in loss tables if that is preferred. “Now that we have both those on view in the cloud, you can overlay the footprint files on top of your exposures, and quickly see it before you even run [the accumulations],” says Higgins. Figure 1: RMS HWind forecast probability of peak gusts greater than 80 miles per hour from Hurricane Ida at 1200UTC August 29, 2021, overlaid on exposure data within the RMS ExposureIQ applicationOne-Stop-Shop This close interaction between HWind and the ExposureIQ application indicates another advantage of the RMS product suite – the use of consistent event response data across the platform so exposure mapping and modeling are all in one place. “The idea is that by having it on the cloud, it is much more performant; you can analyze online portfolios a lot more quickly, and you can get those reports to your board a lot faster than previously,” says Higgins. In contrast to other solutions in the market, which typically use third-party hazard tools and modeling platforms, the RMS suite has a consistent model methodology flowing through the entire product chain. “That's really where the sweet spot of ExposureIQ is – this is all one connected ecosystem,” commented Higgins. “I get my data into ExposureIQ and it is in the same format as Risk Modeler, so I don't need to convert anything. Both products use a consistent financial model too – so you are confident the underlying policy and reinsurance terms are being applied in the same way.” The modular nature of the RMS application ecosystem means that, in addition to hurricane risks, data on perils such as floods, earthquakes, and wildfires are also available – and then processed by the relevant risk modeling tool to give clients insights on their potential losses. “With that indication of where you might expect to experience claims, and how severe those claims might be, you can start to reach out to policyholders to understand if they've been affected.” At this point, clients are then in a good position to start building their claims deployment strategy, preparing claims adjusters to visit impacted sites and briefing reserving and other teams on when to start processing payments. But even before a hurricane has made landfall, clients can make use of forecast wind fields to identify locations that might be affected in advance of the storm and warn policyholders to prepare accordingly. “That can not only help policyholders to protect their property but also mitigate insurance losses as well,” says Higgins. “Similarly, you can use it to apply an underwriting moratorium in advance of a storm. Identify areas that are likely to be impacted, and then feed that into underwriting processes to ensure that no one can write a policy in the region when a storm is approaching.” The First Unified Risk Modeling Platform Previously, before moving to an integrated, cloud-based platform, these tools would likely have been hosted using on-premises servers with all the significant infrastructure costs that implies. Now, in addition to accessing a full suite of products via a single cloud-native platform, RMS clients can also leverage the company’s three decades of modeling expertise, benefiting from a strong foundation of trusted exposure data to help manage their exposures. “A key goal for a lot of people responding to events is initially to understand what locations are affected, how severely they're affected, and what their total exposed limit is, and to inform things like deploying claims adjusters,” says Higgins. And beyond the exposure management function, argues Higgins, it’s about gearing up for the potential pain of those claims, the processes that go around that, and the communication to the board. “These catastrophic events can have a significant impact on a company’s revenue, and the full implications – and any potential mitigation – needs to be well understood.” Find out more about the award-winning ExposureIQ.

Deconstructing Social Inflation

After the loss creep associated with Hurricane Irma in 2017, (re)insurers are keen to quantify how social inflation could exacerbate claims costs in the future. The challenge lies in eliminating the more persistent, longer-term trends, allowing these factors to be explicitly modeled and reducing the “surprise factor” the next time a major storm blows through. A few days after Hurricane Irma passed over Marco Island, Florida, on September 10, 2017, RMS® deployed a reconnaissance team to offer some initial feedback on the damage that was sustained. Most properties on the island had clay tile roofs and while the team noted some dislodged or broken tiles, damage did not appear to be severe. A year later, when Peter Datin, senior director of modeling at RMS, decided to revisit the area, he was shocked by what he saw. “There were so many roofing contractors still on the island, and almost every house seemed to be getting a full roof replacement. We found out that US$900 million worth of roofing permits for repairs had been filed in Marco Island alone.” Trying to find the exact shape and color for tile replacements was a challenge, forcing contractors to replace the entire roof for aesthetic reasons. Then there is Florida's “25 percent rule,” which previously applied to High-Velocity Hurricane Zones in South Florida (Miami-Dade and Broward Counties) before expanding statewide under the 2017 Florida Building Code. Under the rule, if a loss assessor or contractor determines that a quarter or more of the roof has been damaged in the last 12 months, it cannot simply be repaired, and 100 percent must be replaced. This begins to explain why, in the aftermath of Hurricane Irma and to a lesser extent Hurricane Michael in 2018, claims severity and loss creep were such an issue. “We looked at some modeling aspects in terms of the physical meaning of this,” says Datin. “If we were to directly implement an engineering or physics-based approach, what does that mean? How does it impact the vulnerability curve? "We went through this exercise last summer and found that if you hit that threshold of the 25 percent roof damage ratio, particularly for low wind speeds, that's a fourfold increase on your claims. At certain wind speeds, it can therefore have a very material increase on the losses being paid. It’s not quite that straightforward to implement on the vulnerability curve, but it is very significant.” But issues such as the 25 percent rule do not tell the whole story, and in a highly litigious market such as Florida, determining whether a roof needs a complete replacement is not just down to physics. Increasingly, the confluence of additional factors that fall under the broad description of “social inflation” are also having a meaningful impact on the total cost of claims. What Is Social Inflation? Broadly, social inflation refers to all the ways in which insurers’ claims costs rise over and above general economic inflation (i.e., growth in wages and prices), which will influence the cost of repairs and/or replacing damaged property. It therefore captures the growth in costs connected to the following: unanticipated emerging perils associated with, for example, new materials or technologies, shifts in the legal environment, evolving social attitudes and preferences towards equitable risk absorption, and demographic and political developments. (Source: Geneva Association) Florida's “David and Goliath” Law A major driver is the assertive strategies of the plaintiffs' bar, compounded by the three-year window in which to file a claim and the use and potential abuse of practices such as assignment of benefits (AOB). The use of public adjusters and broader societal attitudes towards insurance claiming also need to be taken into consideration. Meanwhile, the expansion of coverage terms and conditions in the loss-free years between 2005 and 2017 and generous policy interpretations play their part in driving up claims frequency and severity. What Is Assignment of Benefits (AOB)? An assignment of benefits, or AOB, is a document signed by a policyholder that allows a third party, such as a water extraction company, a roofer or a plumber to '”stand in the shoes” of the insured and seek payment directly from the policyholder's insurance company for the cost of repairs. AOBs have long been part of Florida’s insurance marketplace. (Source: Florida Office of Insurance Regulation) More recently, the effects of COVID-19 has impacted the cost of repairs, in turn increasing insurers' loss ratios. (Re)insurers naturally want to better understand how social inflation is likely to impact their cost of claims. But determining the impact of social inflation on the “claims signal” is far from simple. From a modeling perspective, the first step is deselecting the different elements that contribute toward social inflation and understanding which trends are longer term in nature. The recently released Version 21 of the RMS North Atlantic Hurricane Models incorporates an alternative view of vulnerability for clients and reflects the changing market conditions applicable to Florida residential lines, including the 25 percent roof replacement rule. However, the effects of social inflation are still largely considered non-modeled. They are removed from available data where possible, during the model development process. Any residual impacts are implicitly represented in the model. “Quantifying the impacts of social inflation is a complex task, partly because of the uncertainty in how long these factors will persist,” says Jeff Waters, senior product manager at RMS. “The question is, going forward, how much of an issue is social inflation really going to be for the next three, five or 10 years? Should we start thinking more about ways in which to explicitly account for these social inflation factors or give model users the ability to manually fold in these different factors? “One issue is that social inflation really ramped up over the last few years,” he continues. “It's especially true in Florida following events like Hurricanes Irma and Michael. At RMS, we have been working hard trying to determine which of these signals are caused by social inflation and which are caused by other things happening in Florida. Certainly, the view of vulnerability in Version 21 starts to reflect these elevated risk factors.” AOB had a clear impact on claims from Irma and Michael. Florida's “David and Goliath” law was intended to level the playing field between policyholders and economically powerful insurers, notes the Insurance Information Institute's Jeff Dunsavage. Instead, the law offered an incentive for attorneys to file thousands of AOB-related suits. The ease with which unscrupulous contractors can “find” damage and make claims within three years of a catastrophe loss has further exacerbated the problem. Waters points out that in 2006 there were only around 400 AOB lawsuits in the market. By 2018, that number had risen to over 135,000. In a decade that had seen very few storms, it was difficult to predict how significant an impact AOB would have on hurricane-related claims, until Irma struck. Of the Irma and Michael claims investigated by RMS, roughly 20 percent were impacted by AOB. “From a claims severity standpoint, the cost of those claims increased up to threefold on average compared to claims that were not affected by AOB," says Waters. Insurers on the Brink The problem is not just limited to recent hurricane events. Due to the Sunshine State's increased litigation, insurers are continuing to face a barrage of AOB non-catastrophe claims, including losses relating to water and roof damage. Reforms introduced in 2019 initially helped rein in the more opportunistic claims, but notifications dialed back up again after attorneys were able to find and exploit loopholes. Amid pressures on the court system due to COVID-19, reform efforts are continuing. In April 2021, the Florida Legislature passed a new law intended to curb market abuse of litigation and roofing contractor practices, among other reforms. Governor Ron DeSantis said the law had been a reaction to “mounting insurance costs” for homeowners. As loss ratios rose, carriers have been passing some of the additional costs back onto the policyholders in the form of additional premiums (around US$680 per family on average). Meanwhile, some carriers have begun to offer policies with limited AOB rights, or none at all, in an effort to get more control over the spiraling situation. “There are some pushes in the legislature to try to curb some of the more litigious behavior on the part of the trial lawyers,” says Matthew Nielsen, senior director, regulatory affairs at RMS. Nielsen thinks the 2021 hurricane season could be telling in terms of separating out some of the more permanent changes in the market where social inflation is concerned. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) still predicts another above-average season in the North Atlantic, but currently does not anticipate the historic level of storm activity seen in 2020. “What's going to happen when the next hurricane makes landfall, and which of these elements are actually going to still be here?” asks Nielsen. “What nobody wants to see again is the kind of chaos that came after 2004 and 2005, when there were questions about the health of the insurance market and what the roles of the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund (FHCF) and Florida Citizens Property Insurance Corporation were going to be.” “Ultimately, we're trying to figure out which of these social inflation signals are going to stick around, and the difficulty is separating the long-term signals from the short-term ones,” he continues. “The 25 percent roof replacement rule is written into legislation, and so that is going to be the new reality going forward. On the other hand, we don't want to include something that is a temporary blip on the radar.”

The Earthquakes That Changed Everything

In the decade since the devastating 2011 Tohoku and Christchurch Earthquakes, risk modelers such as RMS have been proactive in honoring the data generated from these events. It is a process of continuous learning and refinement, explains Chesley Williams and Laura Barksby from RMS, and the journey is still ongoing Within the space of just 17 days in 2011, Christchurch in New Zealand was rocked by an M6.3 earthquake — almost directly beneath the central business district (CBD) — and Japan was reeling from the most powerful earthquake in its history. At RMS, event response and reconnaissance teams were mobilized with the implicit knowledge they were there to do justice to those affected and to gather as much data as possible in order to advance seismic hazard and risk understanding. The tsunami waves triggered by the M9.0 Tohoku Earthquake inundated approximately 532 square kilometers (205 square miles) of the country's northeastern coastline. At its highest point, the waves reached over 15 meters (49 feet) in some localized areas. They overtopped seawalls, destroyed 122,000 buildings with over a million buildings severely or partially damaged, and damaged 230,000 vehicles. The event also triggered level seven meltdowns at Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Station. The disaster at Chernobyl in 1986 was the only previous level seven event. The catastrophe was watched, in horror, in real time on news channels around the world. In total, it caused 15,899 deaths with 2,527 missing. Estimated economic damage totaled US$235 billion. When initiating a risk model update, cat modelers generally start with published national seismic hazard maps, which are typically built on consensus-based research. This represents an important first step — to review the key assumptions in such studies to make sure that they are consistent with the latest data and methods for seismic hazard and risk assessment. “When we developed our RMS® Japan Earthquake Model in 2005, the starting point was the first version of the national seismic hazard maps released in that year,” says Chesley Williams, senior director at RMS. “We had detailed discussions with the Japanese researchers who developed the maps to understand the key assumptions, particularly with a focus on the sources impacting Tokyo.” After the 2011 event, it is now clear that the Japan Trench can produce M9 events. The 2005 national hazard maps were focused on the M7-M8 events that had occurred in the preceding 450+ years. Looking at the geologic record that there have likely been large, possibly M9 events in the past, for example the Jogan Sanriku Earthquake in 869. Honoring the Data So much about both these events in 2011 — the Christchurch Earthquake on February 22 and Tohoku Earthquake on March 11 — was unexpected. Although New Zealand is a highly seismic region, the 2010-11 Canterbury Earthquake Sequence occurred in an area that historically had relatively low seismicity. Prior to the Canterbury Earthquake Sequence there were fewer than 30 earthquakes of magnitude four or greater in Christchurch and the immediate surrounding area. In the last decade, there have been more than 370 earthquakes in this region. The Christchurch Earthquake caused higher-than-expected ground motions and unprecedented liquefaction. As a result, it was the costliest event in the sequence and the second-highest insured loss from earthquake in history, after the Tohoku Earthquake. Japan is also highly seismic, but the Tohoku event occurred on structures that had not shown their full potential during the historical record. The intensity of M9.0 Tohoku was particularly surprising in scale — the highest-ever economic losses from a natural disaster — and the tsunami impact was unprecedented for Japan. “Both Christchurch and Tohoku taught us an awful lot about earthquake risk, including the secondary impacts of earthquakes — tsunami, liquefaction, landslides, nuclear disaster, aftershocks, business interruption, contingent business interruption, and post-event loss amplification,” commented Williams. “They transformed how we think about and model seismic hazard and risk.” New Insights Into Large-Magnitude Events Media coverage of Tohoku clearly showed that the damage in the tsunami induction zones was catastrophic. Once the search and rescue work had been completed, RMS sent a reconnaissance team to Japan to examine tsunami damage and also damage from strong ground shaking, which was extensive. Key observations from this work included that older (pre-1981) concrete buildings often sustained significant damage at high ground motions, traditional wooden homes with heavy tile roofs were more heavily damaged than more modern home construction, and contents damage in high-tech industrial facilities was particularly problematic for production continuity. Tsunami damage from the Tohoku EarthquakeIn the period immediately following a disaster, the Japanese government posts running tallies for the damage statistics as they are collected. This data is invaluable for understanding the scale of damage but also provides important insights with regard to drivers of loss. RMS used these damage statistics during the early event response process to help inform economic and insured loss estimates. In subsequent months, more comprehensive damage statistics compiled by Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism proved vital for refinement of building performance modeling by RMS during strong ground shaking as well as for the development of vulnerability functions for tsunami inundation. Japan has created and maintained what is arguably the best and most dense national seismic network in the world. This network recorded more than 1,000 observations of the ground motions produced by the Tohoku Earthquake. Because large M9+ events are so rare (only five in the last 150 years), this observation dataset is key for understanding the strong ground motions produced by these extremely strong earthquakes. “Prior to this event, modeling of ground motions for events in this magnitude range had to be extrapolated from observation of smaller magnitude events,” says Williams. “Having more data to constrain M9+ ground motions helps refine seismic hazard and risk for all regions that can experience events in this magnitude range. Additionally, the observation data captured the details of the interaction of sedimentary basins and shallow site conditions on ground motion amplitude and frequency content.” The information has allowed RMS to dramatically improve the assessment of site condition impacts (both shallow and deep) to allow for a better assessment of localized interactions of ground motions on structural performance. Following the 2011 events, the Japanese government commissioned a series of comprehensive research studies to better understand earthquake potential for the key subduction zones (i.e., Japan Trench, Kuril Trench, Sagami Trough and Nankai Trough) and key crustal faults. The goal was to extend understanding of the historical record by utilizing the geologic record and providing information on past events over the last several thousand years. Key geologic datasets that were examined included paleotsunami deposits in coastal regions, coastal terraces uplifted in past events and paleoseismic studies to examine past ruptures on faults. The RMS Japan Earthquake Model was informed by all these datasets, allowing for a better representation of the range of events that can occur as well as better constraining the recurrence of future events on these structures. Advances in Tsunami Modeling Prior to the Tohoku event, RMS tsunami solutions had been focused on key tsunami scenario footprints that were developed to allow for an understanding of exposure accumulations at risk. “With the 2011 event and the contribution of approximately 30 percent of the loss from tsunami, it was clear that RMS needed to start providing fully probabilistic tsunami solutions,” said Williams. “The unique characteristics of the Tohoku tsunami event and its generation were key for guiding the RMS tsunami hazard and risk development.” The extremely high fault slip and large ocean bottom deformations highlighted the importance of modeling a range of slip models. RMS has chosen to use analytical slip modeling, and the sampling of alternative slip models for a given earthquake rupture allows for a more comprehensive understanding of tsunami and seismic risk. Tsunami insights from Tohoku also informed tsunami modeling in New Zealand. Following Tohoku, GNS Science, the New Zealand geoscience research institute, updated the maximum magnitude potential for the Hikurangi Subduction Zone to the east of the North Island. This assumption is reflected in the RMS® New Zealand Earthquake HD Model, and when combined with other updates, the larger magnitude has consequential impacts for portfolios with exposure in the capital of Wellington. Lessons in Liquefaction Residents in Christchurch had certainly felt the initial M7.1 Darfield Earthquake on September 4, 2010, some 40 kilometers (25 miles) west of the city, and power and water supplies were disrupted. The event caused moderate damage, the worst of which was to unreinforced masonry chimneys and walls. Damage was also observed in historic buildings. Following the Darfield event, assessments were made to repair the damaged buildings. However, despite the lower magnitude of the February 2011 earthquake, its proximity almost directly beneath the CBD meant that the ground motions were considerable. The Christchurch Earthquake generated widespread liquefaction and was part of an ongoing sequence of events, the largest of which, following February 2011, were M5.9, M5.5 and M5.3. A number of buildings that had been compromised during the September 2010 quake crumbled under the more intense ground motion of February 22, 2011. “It was the way the sequence moved eastward from Darfield to Christchurch so that it was virtually under the CBD that made it so devastating," said Laura Barksby, product manager at RMS. "It occurred in the wrong place at the wrong time.” The Christchurch event exacerbated preexisting damage, as well as damaging previously unscathed structures. Damage was so severe in some areas of Christchurch that a red zone was established, within which it was considered uneconomical to repair buildings, and structures were demolished regardless of their state. In total, the Canterbury Earthquake Sequence caused 185 fatalities and around NZ$40 billion in economic damage, of which an estimated NZ$33-38 billion was insured. The sudden change in seismicity was traumatic for residents and hampered efforts to assess the damage and begin the rebuild and restoration process. Access inside the CBD was restricted as many older structures, mostly unreinforced masonry buildings, were deemed unsafe. In the years immediately following the earthquake, demolitions outnumbered rebuilds by four to one. Aftermath of the Christchurch Earthquake in 2011“There has been a huge societal impact. The CBD was cordoned off and many businesses had to close,” says Barksby. “From a community perspective, they went from years of no earthquakes to almost waiting for the next to happen. The fact that the events were part of a sequence added to that sense of nervousness.” The overall headline, she explains, was the damage caused by liquefaction. “When we think about earthquakes, our immediate thoughts are about the ground shaking, but with Christchurch the focus was the liquefaction. It was responsible for around 30 to 40 percent of the losses, which is considerable.” During an earthquake, the ground motions can cause an increase in water pressure in soil layers beneath the ground. This can cause a reduction in the strength of the soil particles, and they subsequently behave like a liquid, which can cause significant ground deformation. In Christchurch, for buildings with shallow foundations, there was significant damage. One aspect that had not been appreciated prior to Christchurch was the scale of the destruction liquefaction could cause — and the loss it could generate. RMS reconnaissance observed that some buildings experienced no shake damage but considerable liquefaction damage. “The damage was particularly bad along the River Avon in Christchurch," says Barksby. "Due to the lateral displacement, it looked as though some of the buildings had been pulled apart — the Christchurch Earthquake really demonstrated the different types of liquefaction displacement.” This represented an important distinguishing feature when modeling liquefaction risk. “What was seen in Christchurch was a notable difference in the damage severity depending on the liquefaction process that had occurred. There was a correlation between the type of liquefaction displacement and building damage,” said Barksby. “Lateral spreading versus vertical displacement can have very different outcomes when it comes to loss. This distinction is not something we were able to capture before Christchurch, but thanks to data we can now model it at a high resolution and directly relate it to damage at a location.” The liquefaction impact was highly variable, a feature best captured by aerial photographs taken in the immediate aftermath. While some streets were largely unscathed, others looked as though they had been inundated by flood waters from liquefaction expressed at the surface. Barksby added, “We also saw streets with the whole spectrum of liquefaction damage, ranging from none at all to severe damage just a few hundred meters down the road.” Geotechnical engineering experts from around the world seized the opportunity to better understand the hazard, using Christchurch as a liquefaction laboratory. Through its collaboration with the Canterbury Geotechnical Database (now known as the New Zealand Geotechnical Database), RMS was able to analyze borehole data along with claims insights in order to better understand how soil characteristics, water table depth and proximity to water courses influenced the exposure. It was also really important to establish the link on how liquefaction translated into damage, as ultimately this was the main area of concern. Given the significant advances in seismic understanding after Christchurch, New Zealand was chosen as the location for the first RMS high-definition (HD) earthquake model. Released in 2016 and updated in 2020, the model leveraged the surge in data available from the Earthquake Commission (EQC) and GNS Science, among others, together with collaboration partners in the insurance market to offer a more granular view of the hazard and vulnerability. The RMS New Zealand Earthquake HD Model was also the first to include an advanced liquefaction module in addition to landslide, fire following earthquake and probabilistic tsunami. ʺWe applied all the lessons from Christchurch to the rest of the country at a more localized level than had been possible before,” says Barksby. “New Zealand was selected for the first high-definition model because we had so much data arising from the sequence that we knew we could leverage HD methodologies and Cloud-computing technology, plus the country has a sophisticated insurance market.” Barksby describes it as a paradigm shift, with the same underlying principles and framework rolled out to improve the granularity and level of hazard and vulnerability detail captured by the other earthquake models, including those for Japan and North America. Striving for a Resilient Future A decade on from Tohoku and Christchurch, communities in Japan and New Zealand are still coming to terms with the tragedies and how the quakes have shaped their lives. While very large earthquakes remain relatively rare, it is important to understand the potential, including from the associated perils. The return period for earthquakes on major faults or subduction zones is hundreds to thousands of years. Because they are so rare, each earthquake disaster has its own unique characteristics. The events of 2011 were an opportunity to learn and to continue to push the boundaries of earthquake science and seismic engineering. The earthquakes provided a unique opportunity to fundamentally improve the scientific and engineering communities’ understanding of earthquakes and their impacts. RMS has used this opportunity to redefine its perspective on seismic risk in Japan and in New Zealand, and beyond. Chesley Williams concludes: “At RMS, the goal is to implement the best available science, to understand the limitations of the modeling, to apply appropriate uncertainty assumptions and to ensure that we make the best estimate of seismic risk based on the information we have today.”

The Data Driving Wildfire Exposure Reduction

Recent research by RMS® in collaboration with the CIPR and IBHS is helping move the dial on wildfire risk assessment, providing a benefit-cost analysis of science-based mitigation strategies The significant increase in the impact of wildfire activity in North America in the last four years has sparked an evolving insurance problem. Across California, for example, 235,250 homeowners’ insurance policies faced non-renewal in 2019, an increase of 31 percent over the previous year. In addition, areas of moderate to very-high risk saw a 61 percent increase – narrow that to the top 10 counties and the non-renewal rate exceeded 200 percent. A consequence of this insurance availability and affordability emergency is that many residents have sought refuge in the California FAIR (Fair Access to Insurance Requirements) Plan, a statewide insurance pool that provides wildfire cover for dwellings and commercial properties. In recent years, the surge in wildfire events has driven a huge rise in people purchasing cover via the plan, with numbers more than doubling in highly exposed areas. In November 2020, in an effort to temporarily help the private insurance market and alleviate pressure on the FAIR Plan, California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara took the extraordinary step of introducing a mandatory one-year moratorium on insurance companies non-renewing or canceling residential property insurance policies. The move was designed to help the 18 percent of California’s residential insurance market affected by the record 2020 wildfire season. The Challenge of Finding an Exit “The FAIR Plan was only ever designed as a temporary landing spot for those struggling to find fire-related insurance cover, with homeowners ultimately expected to shift back into the private market after a period of time,” explains Jeff Czajkowski, director of the Center for Insurance Policy and Research (CIPR) at the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. “The challenge that they have now, however, is that the lack of affordable cover means for many of those who enter the plan there is potentially no real exit strategy.” The FAIR Plan was only ever designed as a temporary landing spot for those struggling to find fire-related insurance cover, with homeowners ultimately expected to shift back into the private market after a period of time. The challenge that they have now, however, is that the lack of affordable cover means for many of those who enter the plan there is potentially no real exit strategy. Jeff Czajkowski, director of the Center for Insurance Policy and Research (CIPR) at the National Association of Insurance Commissioners These concerns are echoed by Matt Nielsen, senior director of global governmental and regulatory affairs at RMS. “Eventually you run into similar problems to those experienced in Florida when they sought to address the issue of hurricane cover. You simply end up with so many policies within the plan that you have to reassess the risk transfer mechanism itself and look at who is actually paying for it.” The most expedient way to develop an exit strategy is to reduce wildfire exposure levels, which in turn will stimulate activity in the private insurance market and lead to the improved availability and affordability of cover in exposed regions. Yet therein lies the challenge. There is a fundamental stumbling block to this endeavor unique to California’s insurance market and enshrined in regulation. California Code of Regulations, Article 4 – Determination of Reasonable Rates, §2644.5 – Catastrophe Adjustment: “In those insurance lines and coverages where catastrophes occur, the catastrophic losses of any one accident year in the recorded period are replaced by a loading based on a multi-year, long-term average of catastrophe claims. The number of years over which the average shall be calculated shall be at least 20 years for homeowners’ multiple peril fire. …” In effect, this regulation prevents the use of predictive modeling, the mainstay of exposure assessment and accurate insurance pricing, and limits the scope of applicable data to the last 20 years. That might be acceptable if wildfire constituted a relatively stable exposure and if all aspects of the risk could be effectively captured in a period of two decades – but as the last few years have demonstrated, that is clearly not the case. As Roy Wright, president and CEO of the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS), states: “Simply looking back might be interesting, but is it relevant? I don’t mean that the data gathered over the last 20 years is irrelevant, but on its own it is insufficient to understand and get ahead of wildfire risk, particularly when you apply the last four years to the 20-year retrospective, which have significantly skewed the market. That is when catastrophe models provide the analytical means to rationalize such deviations and to anticipate how this threat might evolve.” Simply looking back might be interesting, but is it relevant? I don’t mean that the data gathered over the last 20 years is irrelevant, but on its own it is insufficient to understand and get ahead of wildfire risk, particularly when you apply the last four years to the 20-year retrospective, which have significantly skewed the market. Roy Wright, president and CEO, Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) The insurance industry has long viewed wildfire as an attritional risk, but such a perspective is no longer valid, believes Michael Young, senior director of product management at RMS. “It is only in the last five years that we are starting to see wildfire damaging thousands of buildings in a single event,” he says. “We are reaching the level where the technology associated with cat modeling has become critical because without that analysis you can’t predict future trends. The significant increase in related losses means that it has the potential to be a solvency-impacting peril as well as a rate-impacting one.” Addressing the Insurance Equation “Wildfire by its nature is a hyper-localized peril, which makes accurate assessment very data dependent,” Young continues. “Yet historically, insurers have relied upon wildfire risk scores to guide renewal decisions or to write new business in the wildland-urban interface (WUI). Such approaches often rely on zip-code-level data, which does not factor in environmental, community or structure-level mitigation measures. That lack of ground-level data to inform underwriting decisions means, often, non-renewal is the only feasible approach in highly exposed areas for insurers.” California is unique as it is the only U.S. state to stipulate that predictive modeling cannot be applied to insurance rate adjustments. However, this limitation is currently coming under significant scrutiny from all angles. In recent months, the California Department of Insurance has convened two separate investigatory hearings to address areas including: Insurance availability and affordability Need for consistent home-hardening standards and insurance incentives for mitigation Lack of transparency from insurers on wildfire risk scores and rate justification In support of efforts to demonstrate the need for a more data-driven, model-based approach to stimulating a healthy private insurance market, the CIPR, in conjunction with IBHS and RMS, has worked to facilitate greater collaboration between regulators, the scientific community and risk modelers in an effort to raise awareness of the value that catastrophe models can bring. “The Department of Insurance and all other stakeholders recognize that until we can create a well-functioning insurance market for wildfire risk, there will be no winners,” says Czajkowski. “That is why we are working as a conduit to bring all parties to the table to facilitate productive dialogue. A key part of this process is raising awareness on the part of the regulator both around the methodology and depth of science and data that underpins the cat model outputs.” In November 2020, as part of this process, CIPR, RMS and IBHS co-produced a report entitled “Application of Wildfire Mitigation to Insured Property Exposure.” “The aim of the report is to demonstrate the ability of cat models to reflect structure-specific and community-level mitigation measures,” Czajkowski continues, “based on the mitigation recommendations of IBHS and the National Fire Protection Association’s Firewise USA recognition program. It details the model outputs showing the benefits of these mitigation activities for multiple locations across California, Oregon and Colorado. Based on that data, we also produced a basic benefit-cost analysis of these measures to illustrate the potential economic viability of home-hardening measures.” Applying the Hard Science The study aims to demonstrate that learnings from building science research can be reflected in a catastrophe model framework and proactively inform decision-making around the reduction of wildfire risk for residential homeowners in wildfire zones. As Wright explains, the hard science that IBHS has developed around wildfire is critical to any model-based mitigation drive. “For any model to be successful, it needs to be based on the physical science. In the case of wildfire, for example, our research has shown that flame-driven ignitions account for approximately only a small portion of losses, while the vast majority are ember-driven. “Our facilities at IBHS enable us to conduct full-scale testing using single- and multi-story buildings, assessing components that influence exposure such as roofing materials, vents, decks and fences, so we can generate hard data on the various impacts of flame, ember, smoke and radiant heat. We can provide the physical science that is needed to analyze secondary and tertiary modifiers—factors that drive so much of the output generated by the models.” Our facilities at IBHS enable us to conduct full-scale testing using single- and multi-story buildings, assessing components that influence exposure such as roofing materials, vents, decks and fences, so we can generate hard data on the various impacts of flame, ember, smoke and radiant heat. Roy Wright, president and CEO, Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) To quantify the benefits of various mitigation features, the report used the RMS® U.S. Wildfire HD Model to quantify hypothetical loss reduction benefits in nine communities across California, Colorado and Oregon. The simulated reductions in losses were compared to the costs associated with the mitigation measures, while a benefit-cost methodology was applied to assess the economic effectiveness of the two overall mitigation strategies modeled: structural mitigation and vegetation management. The multitude of factors that influence the survivability of a structure exposed to wildfire, including the site hazard parameters and structural characteristics of the property, were assessed in the model for 1,161 locations across the communities, three in each state. Each structure was assigned a set of primary characteristics based on a series of assumptions. For each property, RMS performed five separate mitigation case runs of the model, adjusting the vulnerability curves based on specific site hazard and secondary modifier model selections. This produced a neutral setting with all secondary modifiers set to zero—no penalty or credit applied—plus two structural mitigation scenarios and two vegetation management scenarios combined with the structural mitigation. The Direct Value of Mitigation Given the scale of the report, although relatively small in terms of the overall scope of wildfire losses, it is only possible to provide a snapshot of some of the key findings. The full report is available to download. Focusing on the three communities in California—Upper Deerwood (high risk), Berry Creek (high risk) and Oroville (medium risk)—the neutral setting produced an average annual loss (AAL) per structure of $3,169, $637 and $35, respectively. Figure 1: Financial impact of adjusting the secondary modifiers to produce both a structural (STR) credit and penaltyFigure 1 shows the impact of adjusting the secondary modifiers to produce a structural (STR) maximum credit (i.e., a well-built, wildfire-resistant structure) and a structural maximum penalty (i.e., a poorly built structure with limited resistance). In the case of Upper Deerwood, the applied credit saw an average reduction of $899 (i.e., wildfire-avoided losses) compared to the neutral setting, while conversely the penalty increased the AAL on average $2,409. For Berry Creek, the figures were a reduction of $222 and an increase of $633. And for Oroville, which had a relatively low neutral setting, the average reduction was $26. Figure 2: Financial analysis of the mean AAL difference for structural (STR) and vegetation (VEG) credit and penalty scenariosIn Figure 2 above, analyzing the mean AAL difference for structural and vegetation (VEG) credit and penalty scenarios revealed a reduction of $2,018 in Upper Deerwood and an increase of $2,511. The data, therefore, showed that moving from a poorly built to well-built structure on average reduced wildfire expected losses by $4,529. For Berry Creek, this shift resulted in an average savings of $1,092, while for Oroville there was no meaningful difference. The authors then applied three cost scenarios based on a range of wildfire mitigation costs: low ($20,000 structural, $25,000 structural and vegetation); medium ($40,000 structural, $50,000 structural and vegetation); and high ($60,000 structural, $75,000 structural and vegetation). Focusing again on the findings for California, the model outputs showed that in the low-cost scenario (and 1 percent discount rate) for 10-, 25- and 50-year time horizons, both structural only as well as structural and vegetation wildfire mitigation were economically efficient on average in the Upper Deerwood, California, community. For Berry Creek, California, economic efficiency for structural mitigation was achieved on average in the 50-year time horizon and in the 25- and 50-year time horizons for structural and vegetation mitigation. Moving the Needle Forward As Young recognizes, the scope of the report is insufficient to provide the depth of data necessary to drive a market shift, but it is valuable in the context of ongoing dialogue. “This report is essentially a teaser to show that based on modeled data, the potential exists to reduce wildfire risk by adopting mitigation strategies in a way that is economically viable for all parties,” he says. “The key aspect about introducing mitigation appropriately in the context of insurance is to allow the right differential of rate. It is to give the right signals without allowing that differential to restrict the availability of insurance by pricing people out of the market.” That ability to differentiate at the localized level will be critical to ending what he describes as the “peanut butter” approach—spreading the risk—and reducing the need to adopt a non-renewal strategy for highly exposed areas. “You have to be able to operate at a much more granular level,” he explains, “both spatially and in terms of the attributes of the structure, given the hyperlocalized nature of the wildfire peril. Risk-based pricing at the individual location level will see a shift away from the peanut-butter approach and reduce the need for widespread non-renewals. You need to be able to factor in not only the physical attributes, but also the actions by the homeowner to reduce their risk. Risk-based pricing at the individual location level will see a shift away from the peanut-butter approach and reduce the need for widespread non-renewals. You need to be able to factor in not only the physical attributes, but also the actions by the homeowner to reduce their risk. Michael Young, senior director of product management at RMS “It is imperative we create an environment in which mitigation measures are acknowledged, that the right incentives are applied and that credit is given for steps taken by the property owner and the community. But to reach that point, you must start with the modeled output. Without that analysis based on detailed, scientific data to guide the decision-making process, it will be incredibly difficult for the market to move forward.” As Czajkowski concludes: “There is no doubt that more research is absolutely needed at a more granular level across a wider playing field to fully demonstrate the value of these risk mitigation measures. However, what this report does is provide a solid foundation upon which to stimulate further dialogue and provide the momentum for the continuation of the critical data-driven work that is required to help reduce exposure to wildfire.”

Data From the Ashes