Reset Filters

Business

- 2022

- 2021

- 2020

- 2019

- 2018

- 2017

- 2016

Earthquake Risk: New Zealand Insurance Sector Experiences Growing Pains

Speed of change around homeowners insurance is gathering pace as insurers move to differential pricing models New Zealand’s insurance sector is undergoing fundamental change as the impact of the NZ$40 billion (US$27 billion) Canterbury Earthquake and more recent Kaikōura disaster spur efforts to create a more sustainable, risk-reflective marketplace. In 2018, EXPOSURE examined risk-based pricing in the region following Tower Insurance’s decision to adopt such an approach to achieve a “fairer and more equitable way of pricing risk.” Since then, IAG, the country’s largest general insurer, has followed suit, with properties in higher-risk areas forecast to see premium hikes, while it also adopts “a conservative approach” to providing insurance in peril-prone areas. “Insurance, unsurprisingly, is now a mainstream topic across virtually every media channel in New Zealand,” says Michael Drayton, a consultant at RMS. “There has been a huge shift in how homeowners insurance is viewed, and it will take time to adjust to the introduction of risk-based pricing.” Another market-changing development is the move by the country’s Earthquake Commission (EQC) to increase the first layer of buildings’ insurance cover it provides from NZ$100,000 to NZ$150,000 (US$68,000 to US$101,000), while lowering contents cover from NZ$20,000 (US$13,500) to zero. These changes come into force in July 2019. Modeling the average annual loss (AAL) impact of these changes based on the updated RMS New Zealand Earthquake Industry Exposure Database shows the private sector will see a marginal increase in the amount of risk it takes on as the AAL increase from the contents exit outweighs the decrease from the buildings cover hike. These findings have contributed greatly to the debate around the relationship between buildings and contents cover. One major issue the market has been addressing is its ability to accurately estimate sums insured. According to Drayton, recent events have seen three separate spikes around exposure estimates. “The first spike occurred in the aftermath of the Christchurch Earthquake,” he explains, “when there was much debate about commercial building values and limits, and confusion relating to sums insured and replacement values. “The second occurred with the move away from open-ended replacement policies in favor of sums insured for residential properties. “Now that the EQC has removed contents cover, we are seeing another spike as the private market broaches uncertainty around content-related replacement values. “There is very much an education process taking place across New Zealand’s insurance industry,” Drayton concludes. “There are multiple lessons being learned in a very short period of time. Evolution at this pace inevitably results in growing pains, but if it is to achieve a sustainable insurance market it must push on through.”

The Future of Risk Management

(Re)insuring new and emerging risks requires data and, ideally, a historical loss record upon which to manage an exposure. But what does the future of risk management look like when so many of these exposures are intangible or unexpected? Sudden and dramatic breakdowns become more likely in a highly interconnected and increasingly polarized world, warns the “Global Risks Report 2019” from the World Economic Forum (WEF). “Firms should focus as much on risk response as on risk mitigation,” advises John Drzik, president of global risk and digital at Marsh, one of the report sponsors. “There’s an inevitability to having a certain number of shock events, and firms should focus on how to respond to fast-moving events with a high degree of uncertainty.” Macrotrends such as climate change, urbanization and digitization are all combining in a way that makes major claims more impactful when things go wrong. But are all low-probability/high-consequence events truly beyond our ability to identify and manage? Dr. Gordon Woo, catastrophist at RMS, believes that in an age of big data and advanced analytics, information is available that can help corporates, insurers and reinsurers to understand the plethora of new and emerging risks they face. “The sources of emerging risk insight are out there,” says Woo. “The challenge is understanding the significance of the information available and ensuring it is used to inform decision-makers.” However, it is not always possible to gain access to the insight needed. “Some of the near-miss data regarding new software and designs may be available online,” says Woo. “For example, with the Boeing 737 Max 8, there were postings by pilots where control problems were discussed prior to the Lion Air disaster of October 2018. Equally, intelligence information on terrorist plots may be available from online terrorist chatter. But typically, it is much harder for individuals to access this information, other than security agencies. “Peter Drucker [consultant and author] was right when he said: ‘If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it,’” he adds. “And this is the issue for (re)insurers when it comes to emerging risks. There is currently not a lot of standardization between risk compliance systems and the way the information is gathered, and corporations are still very reluctant to give information away to insurers.” The Intangibles Protection Gap While traditional physical risks, such as fire and flood, are well understood, well modeled and widely insured, new and emerging risks facing businesses and communities are increasingly intangible and risk transfer solutions are less widely available. While there is an important upside to many technological innovations, for example, there are also downsides that are not yet fully understood or even recognized, thinks Robert Muir-Wood, chief research officer of science and technology at RMS. “Last year’s Typhoon Jebi caused coastal flooding in the Kansai region of Japan,” he says. “There were a lot of cars on the quayside close to where the storm made landfall and many of these just caught on fire. It burnt out a large number of cars that were heading for export. “The reason for the fires was the improved capability of batteries in cars,” he explains. “And when these batteries are immersed in water they burst into flames. So, with this technology you’ve created a whole new peril. There is currently not a lot of standardization between risk compliance systems and the way the information is gathered Gordon Woo RMS “As new technology emerges, new risks emerge,” he concludes. “And it’s not as though the old risks go away. They sort of morph and they always will. Clearly the more that software becomes a critical part of how things function, then there is more of an opportunity for things to go wrong.” From nonphysical-damage business interruption and reputational harm to the theft of intellectual property and a cyber data breach, the ability for underwriters to get a handle on these risks and potential losses is one of the industry’s biggest modern-day challenges. The dearth of products and services for esoteric commercial risks is known as the “intangibles protection gap,” explains Muir-Wood. “There is this question within the whole span of risk management of organizations — of which an increasing amount is intangible — whether they will be able to buy insurance for those elements of their risk that they feel they do not have control over.” While the (re)insurance industry is responding with new products and services geared toward emerging risks, such as cyber, there are some organizational perils, such as reputational risk, that are best addressed by instilling the right risk management culture and setting the tone from the top within organizations, thinks Wayne Ratcliffe, head of risk management at SCOR. “Enterprise risk management is about taking a holistic view of the company and having multidisciplinary teams brainstorming together,” he says. “It’s a tendency of human nature to work in silos in which everyone has their own domain to protect and to work on, but working across an organization is the only way to carry out proper risk management. “There are many causes and consequences of reputational risk, for instance,” he continues. “When I think of past examples where things have gone horribly wrong — and there are so many of them, from Deepwater Horizon to Enron — in certain cases there were questionable ethics and a failure in risk management culture. Companies have to set the tone at the top and then ensure it has spread across the whole organization. This requires constant checking and vigilance.” The best way of checking that risk management procedures are being adhered to is by being really close to the ground, thinks Ratcliffe. “We’re moving too far into a world of emails and communication by Skype. What people need to be doing is talking to each other in person and cross-checking facts. Human contact is essential to understanding the risk.” Spotting the Next “Black Swan” What of future black swans? As per Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns,” so called black swan events are typically those that come from left field. They take everyone by surprise (although are often explained away in hindsight) and have an impact that cascades through economic, political and social systems in ways that were previously unimagined, with severe and widespread consequences. “As (re)insurers we can look at past data, but you have to be aware of the trends and forces at play,” thinks Ratcliffe. “You have to be aware of the source of the risk. In ‘The Big Short’ by Michael Lewis, the only person who really understood the impending subprime collapse was the one who went house-to-house asking people if they were having trouble paying their mortgages, which they were. New technologies are creating more opportunities but they’re also making society more vulnerable to sophisticated cyberattacks Wayne Ratcliffe SCOR “Sometimes you need to go out of the bounds of data analytics into a more intuition-based way of picking up signals where there is no data,” he continues. “You need imagination and to come up with scenarios that can happen based on a group of experts talking together and debating how exposures can connect and interconnect. “It’s a little dangerous to base everything on big data measurement and statistics, and at SCOR we talk about the ‘art and science of risk,’” he continues. “And science is more than statistics. We often need hard science behind what we are measuring. A single-point estimate of the measure is not sufficient. We also need confidence intervals corresponding to a range of probabilities.” In its “Global Risks Report 2019,” the WEF examines a series of “what-if” future shocks and asks if its scenarios, while not predictions, are at least “a reminder of the need to think creatively about risk and to expect the unexpected?” The WEF believes future shocks could come about as a result of advances in technology, the depletion of global resources and other major macrotrends clashing in new and extreme ways. “The world is becoming hyperconnected,” says Ratcliffe. “People are becoming more dependent on social media, which is even shaping political decisions, and organizations are increasingly connected via technology and the internet of things. New technologies are creating more opportunities but they’re also making society more vulnerable to sophisticated cyberattacks. We have to think about the systemic nature of it all.” As governments are pressured to manage the effects of climate change, for instance, will the use of weather manipulation tools — such as cloud seeding to induce or suppress rainfall — result in geopolitical conflict? Could biometrics and AI that recognize and respond to emotions be used to further polarize and/or control society? And will quantum computing render digital cryptography obsolete, leaving sensitive data exposed? The risk of cyberattack was the No. 1 risk identified by business leaders in virtually all advanced economies in the WEF’s “Global Risks Report 2019,” with concern about both data breach and direct attacks on company infrastructure causing business interruption. The report found that cyberattacks continue to pose a risk to critical infrastructure, noting the attack in July 2018 that compromised many U.S. power suppliers. In the attack, state-backed Russian hackers gained remote access to utility- company control rooms in order to carry out reconnaissance. However, in a more extreme scenario the attackers were in a position to trigger widespread blackouts across the U.S., according to the Department of Homeland Security. Woo points to a cyberattack that impacted Norsk Hydro, the company that was responsible for a massive bauxite spill at an aluminum plant in Brazil last year, with a targeted strain of ransomware known as “LockerGoga.” With an apparent motivation to wreak revenge for the environmental damage caused, hackers gained access to the company’s IT infrastructure, including the control systems at its aluminum smelting plants. He thinks a similar type of attack by state-sponsored actors could cause significantly greater disruption if the attackers’ motivation was simply to cause damage to industrial control systems. Woo thinks cyber risk has significant potential to cause a major global shock due to the interconnected nature of global IT systems. “WannaCry was probably the closest we’ve come to a cyber 911,” he explains. “If the malware had been released earlier, say January 2017 before the vulnerability was patched, losses would have been a magnitude higher as the malware would have spread like measles as there was no herd immunity. The release of a really dangerous cyber weapon with the right timing could be extremely powerful.”

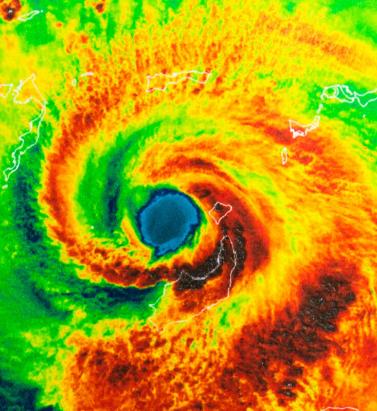

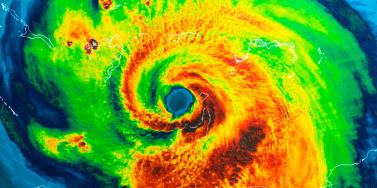

Living in a World of Constant Catastrophes

(Re)insurance companies are waking up to the reality that we are in a riskier world and the prospect of ‘constant catastrophes’ has arrived, with climate change a significant driver In his hotly anticipated annual letter to shareholders in February 2019, Warren Buffett, the CEO of Berkshire Hathaway and acclaimed “Oracle of Omaha,” warned about the prospect of “The Big One” — a major hurricane, earthquake or cyberattack that he predicted would “dwarf Hurricanes Katrina and Michael.” He warned that “when such a mega-catastrophe strikes, we will get our share of the losses and they will be big — very big.” The use of new technology, data and analytics will help us prepare for unpredicted ‘black swan’ events and minimize the catastrophic losses Mohsen Rahnama RMS The question insurance and reinsurance companies need to ask themselves is whether they are prepared for the potential of an intense U.S. landfalling hurricane, a Tōhoku-size earthquake event and a major cyber incident if these types of combined losses hit their portfolio each and every year, says Mohsen Rahnama, chief risk modeling officer at RMS. “We are living in a world of constant catastrophes,” he says. “The risk is changing, and carriers need to make an educated decision about managing the risk. “So how are (re)insurers going to respond to that? The broader perspective should be on managing and diversifying the risk in order to balance your portfolio and survive major claims each year,” he continues. “Technology, data and models can help balance a complex global portfolio across all perils while also finding the areas of opportunity.” A Barrage of Weather Extremes How often, for instance, should insurers and reinsurers expect an extreme weather loss year like 2017 or 2018? The combined insurance losses from natural disasters in 2017 and 2018 according to Swiss Re sigma were US$219 billion, which is the highest-ever total over a two-year period. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria delivered the costliest hurricane loss for one hurricane season in 2017. Contributing to the total annual insurance loss in 2018 was a combination of natural hazard extremes, including Hurricanes Michael and Florence, Typhoons Jebi, Trami and Mangkhut, as well as heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, floods and convective storms. While it is no surprise that weather extremes like hurricanes and floods occur every year, (re)insurers must remain diligent about how such risks are changing with respect to their unique portfolios. Looking at the trend in U.S. insured losses from 1980–2018, the data clearly shows losses are increasing every year, with climate-related losses being the primary drivers of loss, especially in the last four decades (even allowing for the fact that the completeness of the loss data over the years has improved). Measuring Climate Change With many non-life insurers and reinsurers feeling bombarded by the aggregate losses hitting their portfolios each year, insurance and reinsurance companies have started looking more closely at the impact that climate change is having on their books of business, as the costs associated with weather-related disasters increase. The ability to quantify the impact of climate change risk has improved considerably, both at a macro level and through attribution research, which considers the impact of climate change on the likelihood of individual events. The application of this research will help (re)insurers reserve appropriately and gain more insight as they build diversified books of business. Take Hurricane Harvey as an example. Two independent attribution studies agree that the anthropogenic warming of Earth’s atmosphere made a substantial difference to the storm’s record-breaking rainfall, which inundated Houston, Texas, in August 2017, leading to unprecedented flooding. In a warmer climate, such storms may hold more water volume and move more slowly, both of which lead to heavier rainfall accumulations over land. Attribution studies can also be used to predict the impact of climate change on the return-period of such an event, explains Pete Dailey, vice president of model development at RMS. “You can look at a catastrophic event, like Hurricane Harvey, and estimate its likelihood of recurring from either a hazard or loss point of view. For example, we might estimate that an event like Harvey would recur on average say once every 250 years, but in today’s climate, given the influence of climate change on tropical precipitation and slower moving storms, its likelihood has increased to say a 1-in-100-year event,” he explains. We can observe an incremental rise in sea level annually — it’s something that is happening right in front of our eyes Pete Dailey RMS “This would mean the annual probability of a storm like Harvey recurring has increased more than twofold from 0.4 percent to 1 percent, which to an insurer can have a dramatic effect on their risk management strategy.” Climate change studies can help carriers understand its impact on the frequency and severity of various perils and throw light on correlations between perils and/or regions, explains Dailey. “For a global (re)insurance company with a book of business spanning diverse perils and regions, they want to get a handle on the overall effect of climate change, but they must also pay close attention to the potential impact on correlated events. “For instance, consider the well-known correlation between the hurricane season in the North Atlantic and North Pacific,” he continues. “Active Atlantic seasons are associated with quieter Pacific seasons and vice versa. So, as climate change affects an individual peril, is it also having an impact on activity levels for another peril? Maybe in the same direction or in the opposite direction?” Understanding these “teleconnections” is just as important to an insurer as the more direct relationship of climate to hurricane activity in general, thinks Dailey. “Even though it’s hard to attribute the impact of climate change to a particular location, if we look at the impact on a large book of business, that’s actually easier to do in a scientifically credible way,” he adds. “We can quantify that and put uncertainty around that quantification, thus allowing our clients to develop a robust and objective view of those factors as a part of a holistic risk management approach.” Of course, the influence of climate change is easier to understand and measure for some perils than others. “For example, we can observe an incremental rise in sea level annually — it’s something that is happening right in front of our eyes,” says Dailey. “So, sea-level rise is very tangible in that we can observe the change year over year. And we can also quantify how the rise of sea levels is accelerating over time and then combine that with our hurricane model, measuring the impact of sea-level rise on the risk of coastal storm surge, for instance.” Each peril has a unique risk signature with respect to climate change, explains Dailey. “When it comes to a peril like severe convective storms — tornadoes and hail storms for instance — they are so localized that it’s difficult to attribute climate change to the future likelihood of such an event. But for wildfire risk, there’s high correlation with climate change because the fuel for wildfires is dry vegetation, which in turn is highly influenced by the precipitation cycle.” Satellite data from 1993 through to the present shows there is an upward trend in the rate of sea-level rise, for instance, with the current rate of change averaging about 3.2 millimeters per year. Sea-level rise, combined with increasing exposures at risk near the coastline, means that storm surge losses are likely to increase as sea levels rise more quickly. “In 2010, we estimated the amount of exposure within 1 meter above the sea level, which was US$1 trillion, including power plants, ports, airports and so forth,” says Rahnama. “Ten years later, the exact same exposure was US$2 trillion. This dramatic exposure change reflects the fact that every centimeter of sea-level rise is subjected to a US$2 billion loss due to coastal flooding and storm surge as a result of even small hurricanes. “And it’s not only the climate that is changing,” he adds. “It’s the fact that so much building is taking place along the high-risk coastline. As a result of that, we have created a built-up environment that is actually exposed to much of the risk.” Rahnama highlighted that because of an increase in the frequency and severity of events, it is essential to implement prevention measures by promoting mitigation credits to minimize the risk. He says: “How can the market respond to the significant losses year after year. It is essential to think holistically to manage and transfer the risk to the insurance chain from primary to reinsurance, capital market, ILS, etc.,” he continues. “The art of risk management, lessons learned from past events and use of new technology, data and analytics will help to prepare for responding to unpredicted ‘black swan’ type of events and being able to survive and minimize the catastrophic losses.” Strategically, risk carriers need to understand the influence of climate change whether they are global reinsurers or local primary insurers, particularly as they seek to grow their business and plan for the future. Mergers and acquisitions and/or organic growth into new regions and perils will require an understanding of the risks they are taking on and how these perils might evolve in the future. There is potential for catastrophe models to be used on both sides of the balance sheet as the influence of climate change grows. Dailey points out that many insurance and reinsurance companies invest heavily in real estate assets. “You still need to account for the risk of climate change on the portfolio, whether you’re insuring properties or whether you actually own them, there’s no real difference.” In fact, asset managers are more inclined to a longer-term view of risk when real estate is part of a long-term investment strategy. Here, climate change is becoming a critical part of that strategy. “What we have found is that often the team that handles asset management within a (re)insurance company is an entirely different team to the one that handles catastrophe modeling,” he continues. “But the same modeling tools that we develop at RMS can be applied to both of these problems of managing risk at the enterprise level. “In some cases, a primary insurer may have a one-to-three-year plan, while a major reinsurer may have a five-to-10-year view because they’re looking at a longer risk horizon,” he adds. “Every time I go to speak to a client — whether it be about our U.S. Inland Flood HD Model or our North America Hurricane Models — the question of climate change inevitably comes up. So, it’s become apparent this is no longer an academic question, it’s actually playing into critical business decisions on a daily basis.” Preparing for a Low-carbon Economy Regulation also has an important role in pushing both (re)insurers and large corporates to map and report on the likely impact of climate change on their business, as well as explain what steps they have taken to become more resilient. In the U.K., the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and Bank of England have set out their expectations regarding firms’ approaches to managing the financial risks from climate change. Meanwhile, a survey carried out by the PRA found that 70 percent of U.K. banks recognize the risk climate change poses to their business. Among their concerns are the immediate physical risks to their business models — such as the exposure to mortgages on properties at risk of flood and exposure to countries likely to be impacted by increasing weather extremes. Many have also started to assess how the transition to a low-carbon economy will impact their business models and, in many cases, their investment and growth strategy. “Financial policymakers will not drive the transition to a low-carbon economy, but we will expect our regulated firms to anticipate and manage the risks associated with that transition,” said Bank of England Governor Mark Carney, in a statement. The transition to a low-carbon economy is a reality that (re)insurance industry players will need to prepare for, with the impact already being felt in some markets. In Australia, for instance, there is pressure on financial institutions to withdraw their support from major coal projects. In the aftermath of the Townsville floods in February 2019 and widespread drought across Queensland, there have been renewed calls to boycott plans for Australia’s largest thermal coal mine. To date, 10 of the world’s largest (re)insurers have stated they will not provide property or construction cover for the US$15.5 billion Carmichael mine and rail project. And in its “Mining Risk Review 2018,” broker Willis Towers Watson warned that finding insurance for coal “is likely to become increasingly challenging — especially if North American insurers begin to follow the European lead.”

IFRS17: Under the Microscope

How new accounting standards could reduce demand for reinsurance as cedants are forced to look more closely at underperforming books of business They may not be coming into effect until January 1, 2021, but the new IFRS 17 accounting standards are already shaking up the insurance industry. And they are expected to have an impact on the January 1, 2019, renewals as insurers ready themselves for the new regime. Crucially, IFRS 17 will require insurers to recognize immediately the full loss on any unprofitable insurance business. “The standard states that reinsurance contracts must now be valued and accounted for separate to the underlying contracts, meaning that traditional ‘netting down’ (gross less reinsured) and approximate methods used for these calculations may no longer be valid,” explained PwC partner Alex Bertolotti in a blog post. “Even an individual reinsurance contract could be material in the context of the overall balance sheet, and so have the potential to create a significant mismatch between the value placed on reinsurance and the value placed on the underlying risks,” he continued. “This problem is not just an accounting issue, and could have significant strategic and operational implications as well as an impact on the transfer of risk, on tax, on capital and on Solvency II for European operations.” In fact, the requirements under IFRS 17 could lead to a drop in reinsurance purchasing, according to consultancy firm Hymans Robertson, as cedants are forced to question why they are deriving value from reinsurance rather than the underlying business on unprofitable accounts. “This may dampen demand for reinsurance that is used to manage the impact of loss making business,” it warned in a white paper. Cost of Compliance The new accounting standards will also be a costly compliance burden for many insurance companies. Ernst & Young estimates that firms with over US$25 billion in Gross Written Premium (GWP) could be spending over US$150 million preparing for IFRS 17. Under the new regime, insurers will need to account for their business performance at a more granular level. In order to achieve this, it is important to capture more detailed information on the underlying business at the point of underwriting, explained Corina Sutter, director of government and regulatory affairs at RMS. This can be achieved by deploying systems and tools that allow insurers to capture, manage and analyze such granular data in increasingly high volumes, she said. “It is key for those systems or tools to be well-integrated into any other critical data repositories, analytics systems and reporting tools. “From a modeling perspective, analyzing performance at contract level means precisely understanding the risk that is being taken on by insurance firms for each individual account,” continued Sutter. “So, for P&C lines, catastrophe risk modeling may be required at account level. Many firms already do this today in order to better inform their pricing decisions. IFRS 17 is a further push to do so. “It is key to use tools that not only allow the capture of the present risk, but also the risk associated with the future expected value of a contract,” she added. “Probabilistic modeling provides this capability as it evaluates risk over time.”

When the Lights Went Out

How poor infrastructure, grid blackouts and runaway business interruption has hampered Puerto Rico’s recovery in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria As the 2018 North Atlantic hurricane season continues, Puerto Rico has yet to recover from destructive events of the previous year. In September 2017, Category 4 Hurricane Maria devastated several Caribbean islands, including Puerto Rico, and left a trail of destruction in its path. For many, Maria was one of the worst natural catastrophes to hit a U.S. territory, causing an estimated US$65 billion to US$115 billion in damage and claiming as many as 4,500 to 5,000 lives. The damage wrought has further strained the island’s sluggish economy. Puerto Rico had over US$70 billion in public debt when Maria hit. Economic forecasts for 2018 to 2020, considering the impact of Hurricane Maria, suggest Puerto Rico’s GDP will decline by 7 to 8 percent in 2018 and likely remain in a negative range of 5 to 7 percent for the next few years. “Resilience is also about the financial capacity to come back and do the reconstruction work” Pooya Sarabandi RMS Power outages, business interruption (BI) and contingent BI (CBI) — including supply chain disruption — have hampered the economy’s recovery. “Resilience is also about the financial capacity to come back and do the reconstruction work,” explains Pooya Sarabandi, global head of data analy- tics at RMS. “You’re now into this chicken- and-egg situation where the Puerto Rican government already has a lot of public debt and doesn’t have reserves, and meanwhile the federal U.S. government is only willing to provide a certain level of funding.” Maria’s devastating impact on Puerto Rico demonstrates the lasting effect a major catastrophe can have when it affects a small, isolated region with a concentrated industry and lack of resilience in infrastructure and lifelines. Whereas manufacturers based on the U.S. mainland have contingencies to tap into — the workforce, raw materials and components, and infrastructure in other parts of the country during times of need — there is not the same opportunity to do this on an island, explains Sarabandi. Rolling Blackouts Following Maria’s landfall, residences and businesses experienced power outages throughout the island. Severe physical damage to electric power generation plants, transmission and distribution systems — including solar and wind power generation plants — plunged the island into a prolonged period of rolling blackouts. Around 80 percent of utility poles were damaged in the event, leaving most of the island without electricity. Two weeks after the storm, 90 percent of the island was still without power. A month on, roughly 85 percent of customers were not connected to the power grid. Three months later, this figure was reported to be about half of Puerto Ricans. And finally, after six months, about 15 percent of residents did not have electricity. “There’s no real damage on the grid itself,” says Victor Roldan, head of Caribbean and Latin America at RMS. “Most of the damage is on the distribution lines around the island. Where they had the better infrastructure in the capital, San Juan, they were able to get it back up and running in about two weeks. But there are still parts of the island without power due to bad distribution infrastructure. And that’s where the business interruption is mostly coming from. “There are reports that 50 percent of all Maria claims for Puerto Rico will be CBI related,” adds Roldan. “Insurers were very competitive, and CBI was included in commercial policies without much thought to the consequences. Policyholders probably paid a fifth of the premiums they should have, way out of kilter with the risk. The majority of CBI claims will be power related, the businesses didn’t experience physical damage, but the loss of power has hit them financially.” Damage to transportation infrastructure, including railways and roads, only delayed the pace of recovery. The Tren Urbano, the island’s only rail line that serves the San Juan metropolitan area (where roughly 60 percent of Puerto Ricans live), started limited service for the first time almost three months after Hurricane Maria struck. There were over 1,500 reported instances of damage to roads and bridges across the island. San Juan’s main airport, the busiest in the Caribbean, was closed for several weeks. A Concentration of Risk Roughly half of Puerto Rico’s economy is based on manufacturing activities, with around US$50 billion in GDP coming from industries such as pharmaceutical, medical devices, chemical, food, beverages and tobacco. Hurricane Maria had a significant impact on manufacturing output in Puerto Rico, particularly on the pharmaceutical and medical devices industries, which is responsible for 30 percent of the island’s GDP. According to Anthony Phillips, chairman of Willis Re Latin America and Caribbean, the final outcome of the BI loss remains unknown but has exceeded expectations due to the length of time in getting power reinstalled. “It’s hard to model the BI loss when you depend on the efficiency of the power companies,” he says. “We used the models and whilst personal lines appeared to come in within expectations, commercial lines has exceeded them. This is mainly due to BI and the inability of the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) to get things up and running.” Home to more than 80 pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities, many of which are operated by large multinational companies, Puerto Rico’s pharmaceutical hub was a significant aggregation of risk from a supply chain and insurance perspective. Although only a few of the larger pharmaceutical plants were directly damaged by the storm, operations across the sector were suspended or reduced, in some cases for weeks or even months, due to power outages, lack of access and logistics. “The perception of the Business Interruption insurers anticipated, versus the reality, was a complete mismatch” Mohsen Rahnama RMS “The perception of the BI insurers anticipated, versus the reality, was a complete mismatch,” says Mohsen Rahnama, chief risk modeling officer at RMS. “All the big names in pharmaceuticals have operations in Puerto Rico because it’s more cost- effective for production. And they’re all global companies and have backup processes in place and cover for business interruption. However, if there is no diesel on the island for their generators, and if materials cannot get to the island, then there are implications across the entire chain of supply.” While most of the plants were equipped with backup power generation units, manu- facturers struggled due to long-term lack of connection to the island’s only power grid. The continuous functioning of on-site generators was not only key to resuming production lines, power was also essential for refrigeration and storage of the pharmaceuticals. Five months on, 85 medicines in the U.S. were classified by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as “in shortage.” There are several reasons why Puerto Rico’s recovery stalled. Its isolation from the U.S. mainland and poor infrastructure were both key factors, highlighted by comparing the island’s recovery to recovery operations following U.S. mainland storms, such as Hurricane Harvey in Texas last year and 2012’s Superstorm Sandy. Not only did Sandy impact a larger area when it hit New York and New Jersey, it also caused severe damage to all transmission and distribution systems in its path. However, recovery and restoration took weeks, not months. It is essential to incorporate the vulnerabilities created by an aggregation of risk, inadequate infrastructure and lack of contingency options into catastrophe and pricing models, thinks Roldan. “There is only one power company and the power company is facing bankruptcy,” he says. “It hasn’t invested in infrastructure in years. Maria wasn’t even the worst-case scenario because it was not a direct hit to San Juan. So, insurers need to be prepared and underwriting business interruption risks in a more sophisticated manner and not succumbing to market pressures.” CBI Impact on Hospitality and Tourism Large-magnitude, high-consequence events have a lasting impact on local populations. Businesses can face increased levels of disruption and loss of revenue due to unavailability of customers, employees or both. These resourcing issues need to be properly considered in the scenario-planning stage, particularly for sectors such as hospitality and tourism. Puerto Rico’s hospitality and tourism sectors are a significant source of its GDP. While 69 percent of hotels and 61 percent of casinos were operational six weeks after Maria struck, according to the Puerto Rico Tourism Company, other factors continued to deter visitors. It was not until the end of February 2018, five months after the event, that roughly 80 percent of Puerto Rico’s hotels and restaurants were back in business with tourists returning to the island. This suggests a considerable loss of income due to indirect business interruption in the hospitality and tourism industry.

What One Thing Would Help Reinsurers Get Closer to the Original Risk?

In each edition of EXPOSURE we ask three experts for their opinion on how they would tackle a major risk and insurance challenge. This issue, we consider how (re)insurers can gain more insight into the original risk, and in so doing, remove frictional costs. As our experts Kieran Angelini-Hurll, Will Curran and Luzi Hitz note, more insight does not necessarily mean disintermediation. Kieran Angelini-Hurll CEO, Reinsurance at Ed The reduction of frictional costs would certainly help. At present, there are too many frictional costs between the reinsurer and the original risk. The limited amount of data available to reinsurers on the original risks is also preventing them from getting a clear picture. A combination of new technology and a new approach from brokers can change this. First, the technology. A trading platform which reduces frictional costs by driving down overheads will bridge the gap between reinsurance capital and the insured. However, this platform can only work if it provides the data which will allow reinsurers to better understand this risk. Arguably, the development of such a platform could be achieved by any broker with the requisite size, relevance and understanding of reinsurers’ appetites. Brokers reluctant to share data will watch their business migrate to more disruptive players However, for most, their business models do not allow for it. Their size stymies innovation and they have become dependent on income derived from the sale of data, market-derived income and ‘facilitization’. These costs prevent reinsurers from getting closer to the risk. They are also unsustainable, a fact that technology will prove. A trading platform which has the potential to reduce costs for all parties, streamline the throughput of data, and make this information readily and freely available could profoundly alter the market. Brokers that continue to add costs and maintain their reluctance to share data will be forced to evolve or watch their business migrate to leaner, more disruptive players. Brokers which are committed to marrying reinsurance capital with risk, regardless of its location and that deploy technology, can help overcome the barriers put in place by current market practices and bring reinsurers closer to the original risk. Will Curran Head of Reinsurance, Tokio Marine Kiln, London More and more, our customers are looking to us as their risk partners, with the expectation that we will offer far more than a transactional risk transfer product. They are looking for pre-loss services, risk advisory and engineering services, modeling and analytical capabilities and access to our network of external experts, in addition to more traditional risk transfer. As a result of offering these capabilities, we are getting closer to the original risk, through our discussions with cedants and brokers, and our specialist approach to underwriting. Traditional carriers are able to differentiate by going beyond vanilla risk transfer The long-term success of reinsurers needs to be built on offering more than being purely a transactional player. To a large extent, this has been driven by the influx of non-traditional capital into the sector. Whereas these alternative property catastrophe reinsurance providers are offering a purely transactional product, often using parametric or industry-loss triggers to simplify the claims process in their favor, traditional carriers are able to differentiate by going beyond vanilla risk transfer. Demand for risk advice and pre-loss services are particularly high within specialist and emerging risk classes of business. Cyber is a perfect example of this, where we work closely with our corporate and insurance clients to help them improve their resilience to cyber-attack and to plan their response in the event of a breach. Going forward, successful reinsurance companies will be those that invest time and resources in becoming true risk partners. In an interconnected and increasingly complex world, where there is a growing list of underinsured exposures, risk financing is just one among many service offerings in the toolkit of specialist reinsurers. Luzi Hitz CEO, PERILS AG The nature of reinsurance means the reinsurer is inherently further away from the underlying risk than most other links in the value chain. The risk is introduced by the original insured, and is transferred into the primary market before reaching the reinsurer – a process normally facilitated by reinsurance intermediaries. I am wary of efforts to shortcut or circumvent this established multi-link chain to reduce the distance between reinsurer and the underlying risk. The reinsurer in many cases lacks the granular insight found earlier in the process required to access the risk directly. What we need is a more cooperative relationship between reinsurer and insurer in developing risk transfer products. Too often the reinsurers act purely as capital providers in the chain and from the source risk, viewing it almost as an abstract concept within the overall portfolio. The focus should be on how to bring all parties to the risk closer together By collaborating on the development of insurance products, not only will it help create greater alignment of interest based on a better understanding of the risk relationship, but also prove beneficial to the entire insurance food chain. It will make the process more efficient and cost effective, and hopefully see the risk owners securing the protection they want. In addition, it is much more likely to stimulate product innovation and growth, which is badly needed in many mature markets. The focus in my opinion should not be on how to bring the reinsurer closer to the risk, but rather on how to bring all parties to the risk closer together. What I am saying is not new, and it is certainly something which many larger reinsurers have been striving to achieve for years. And while there is evidence of this more collaborative approach between insurers and reinsurers gaining traction, there is still a very long way to go.

Efficiency Breeds Value

Insurers must harness data, technology and human capital if they are to operate more efficiently and profitably in the current environment, but as AXIS Capital’s Albert Benchimol tells EXPOSURE, offering better value to clients may be a better long-term motive for becoming more efficient. Efficiency is a top priority for insurers the world over as they bid to increase margins, reduce costs and protect profitability in the competitive heat of the enduring soft market. But according to AXIS Capital president and CEO Albert Benchimol, there is a broader, more important and longer-term challenge that must also be addressed through the ongoing efficiency drive: value for money. “When I think of value, I think of helping our clients and partners succeed in their own endeavors. This means providing quick and responsive service, creative policy structures that address our customers’ coverage needs, best-in-class claims handling and trusting our people to pursue their own entrepreneurial goals,” says Benchimol. “While any one insurance policy may in itself offer good value, when aggregated, insurance is not necessarily seen as good value by clients. Our industry as a whole needs to deliver a better value proposition — and that means that all participants in the value chain will need to become much more efficient.” According to Benchimol — who prior to being appointed CEO of AXIS in 2012 served as the Bermuda-based insurance group’s CFO and also held senior executive positions at Partner Re, Reliance Group and Bank of Montreal — the days of paying out US$0.55-$0.60 in claims for every dollar of premium paid are over. “We need to start framing our challenge as delivering a 70 percent-plus loss ratio within a low 90s combined ratio,” he asserts. “Every player in the value chain needs to adopt efficiency-enhancing technology to lower our costs and pass those savings on to the customer.” With a surfeit of capital making it unlikely the insurance industry will return to its traditional cyclical nature any time soon, Benchimol says these changes have to be adopted for the long term. “Insurers have to evaluate their portfolios and product offerings to match customer needs with marketplace realities. We will need to develop new products to meet emerging demand; offer better value in the eyes of insureds; apply data, analytics and technology to all facets of our business; and become much more efficient,” he explains. Embracing Technology The continued adoption and smarter use of data will be central to achieving this goal. “We’ve only begun to scratch the surface of what data we can access and insights we can leverage to make better, faster decisions throughout the risk transfer value chain,” Benchimol says. “If we use technology to better align our operations and costs with our customers’ needs and expectations, we will create and open-up new markets because potential insureds will see more value in the insurance product.” “I admire companies that constantly challenge themselves and that are driven by data to make informed decisions — companies that don’t rest on their laurels and don’t accept the status quo” Technology, data and analytics have already brought improved efficiencies to the insurance market. This has allowed insurers to focus their efforts on targeted markets and develop applications to deliver improved, customized purchasing experiences and increase client satisfaction and engagement, Benchimol notes. The introduction of data modeling, he adds, has also played a key role in improving economic protection, making it easier for (re)insurance providers to evaluate risks and enter new markets, thereby increasing the amount of capacity available to protect insureds. “While this can sometimes raise pricing pressures, it has a positive benefit of bringing more affordable capacity to potential customers. This has been most pronounced in the development of catastrophe models in underinsured emerging markets, where capital hasn’t always been available in the past,” he says. The introduction of models made these markets more attractive to capital providers which, in turn, makes developing custom insurance products more cost-effective and affordable for both insurers and their clients, Benchimol explains. However, there is no doubt the insurance industry has more to do if it is not only to improve its own profitability and offerings to customers, but also to stave off competition from external threats, such as disruptive innovators in the FinTech and InsurTech spheres. Strategic Evolution “The industry’s inefficiencies and generally low level of customer satisfaction make it relatively easy prey for disruption,” Benchimol admits. However, he believes that the regulated and highly capital-intensive nature of insurance is such that established domain leaders will continue to thrive if they are prepared to beat innovators at their own game. “We need to move relatively quickly, as laggards may have a difficult time catching up,” he warns. “In order to thrive in the disruptive market economy, market leaders must take intelligent risks. This isn’t easy, but is absolutely necessary,” Benchimol says. “I admire companies that constantly challenge themselves and that are driven by data to make informed decisions — companies that don’t rest on their laurels and don’t accept the status quo.” “We need to start framing our challenge as delivering a 70-percent plus loss ratio within a low 90s combined ratio” Against the backdrop of a rapidly evolving market and transformed business environment, AXIS took stock of its business at the start of 2016, evaluating its key strengths and reflecting on the opportunities and challenges in its path. What followed was an important strategic evolution. “Over the course of the year we implemented a series of strategic initiatives across the business to drive long-term growth and ensure we deliver the most value to our clients, employees and shareholders,” Benchimol says. “This led us to sharpen our focus on specialty risk, where we believe we have particular expertise. We implemented new initiatives to even further enhance the quality of our underwriting. We invested more in our data and analytics capabilities, expanded the focus in key markets where we feel we have the greatest relevance, and took action to acquire firms that allow us to expand our leadership in specialty insurance, such as our acquisition of specialty aviation insurer and reinsurer Aviabel and our recent offer to acquire Novae.” Another highlight for AXIS in 2016 was the launch of Harrington Re, co-founded with the Blackstone Group. “At AXIS, our focus on innovation also extends to how we look at alternative funding sources and our relationship with third-party capital, which centers on matching the right risk with the right capital,” Benchimol explains. “We currently have a number of alternative capital sources that complement our balance sheet and enable us to deliver enhanced capacity and tailored solutions to our clients and brokers.” Benchimol believes a significant competitive advantage for AXIS is that it is still small enough to be agile and responsive to customers’ needs, yet large enough to take advantage of its global capabilities and resources in order to help clients manage their risks. But like many of his competitors, Benchimol knows future success will be heavily reliant on how well AXIS melds human expertise with the use of data and technology. “We need to combine our ingenuity, innovation and values with the strength, speed and intelligence offered by technology, data and analytics. The ability to combine these two great forces — the art and science of insurance — is what will define the insurer of the future,” Benchimol states. The key, he believes, is to empower staff to make informed, data-driven decisions. “The human elements that are critical to success in the insurance industry are, among others: knowledge, creativity, service and commitment to our clients and partners. We need to operate within a framework that utilizes technology to provide a more efficient customer experience and is underpinned by enhanced data and analytics capabilities that allow us to make informed, intelligent decisions on behalf of our clients.” However, Benchimol insists insurers must embrace change while holding on to the traditional principles that underpinned insurance in the analog age, as these same principles must continue to do so into the future. “We must harness technology for good causes, while remaining true to the core values and universal strengths of our industry — a passion for helping people when they are down, a creativity in structuring products, and the commitment to keeping the promise we make to our clients to help them mitigate risks and ensure the security of their assets,” he says. “We must not forget these critical elements that comprise the heart of the insurance industry.”