August 14, 2017

Just Tell Me Whether Andrew is Coming

On Saturday, August 22, 1992, I met with Herb Saffir (coauthor of the Saffir-Simpson Scale) in his Coral Gables office, south of downtown Miami, discussing a manual for post-storm damage investigation. I was also due to be the hurricane scientist member of a panel that Herb was chairing for the American Society of Civil Engineers. As the meeting ended it became apparent that Andrew, which had become a hurricane that morning, was approaching the Bahamas and was not going to recurve northward as hoped. It was coming right at us.

My home was in Coconut Grove, about three miles south of downtown Miami. I called my wife and told her to get to the Publix supermarket since a hurricane warning was imminent and we knew from earlier storms that there would soon be a run on supplies. I headed off to Home Depot for plywood and wondered how I could protect the house and still make my scheduled research reconnaissance flight into the storm on Sunday, working on one of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) P3 Hurricane Hunter aircraft. As a hurricane wind specialist, I would be monitoring the wind field and radar displays over a proposed ten-hour mission. That mission was scrubbed when it became apparent that the aircraft would need to be evacuated from their base at Miami International Airport.

Instead, the Air Force Reserves of the 53rd Weather Squadron out of Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, flew a C-130 into the storm late Sunday, while I thankfully completed my shutters and we accommodated some friends (and their pets) who lived in a storm surge evacuation zone. Our home was near 20 feet (6 meters) above sea level on the coastal ridge in Coconut Grove, so flooding would not be a problem.

Well, Andrew hit overnight, and by 9 a.m. Monday morning, we seemed to be OK. Lots of trees were down and the power out but the house was intact with just a few broken roof tiles and one cracked window. We walked down to Biscayne Bay to check on the flooding and took some pictures, feeling the excitement of viewing a dramatically changed landscape. The mood changed when we received a call (yes, the phones were working even though there was no power) from another friend who was crying and upset about damage further south. We spent hours picking our way about 10 miles south to find that our guest’s home in “Whispering Pines” was within ground zero of the northern eyewall of Andrew. Their roof covering was peeled, double front doors were blown in, and all their living room furniture had been blasted through a sliding glass door into their pool.

Our friends were in shock and time was short due to an impending curfew so we made our way to the main north-south drag, U.S. Route 1 or Dixie Highway (difficult since all the street signs were blown down) for the drive back to Coconut Grove. We were marveling at the lack of any organized response, when we noticed a white school bus making its way southward on US 1. We couldn’t hold back tears when we saw that the first responders were the City of Charleston Police Department. This was pay back from 1989, when Charleston was hit by Hurricane Hugo and Miami Metro-Dade County helped in the response.

Kate Hale, Emergency Director, Miami-Dade County – interviewed by local TV with regards to response to Hurricane AndrewOvernight more than 200,000 were left homeless without power and with few supplies. Fifteen died from blunt trauma or drowning in the storm surge. It took days for significant relief to arrive with Kate Hale, the Miami-Dade County emergency director pleading “Where the hell is the cavalry on this one?” Despite the slow pace of response, it was amazing how the communities of South Florida pulled together to help each other out, with neighbors helping each other and sharing supplies.

It was also amazing that the Air Force crew on that C130 flew all night, monitoring Andrew as it strengthened through landfall and continuing to fly a hazardous pattern over land as the storm progressed inland. For several months’ afterwards, my team at NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division worked to piece together data and reconstruct Andrew’s wind field. We visited sites with incredible damage where lives were lost. The public sent data in and we worked with wind engineering colleagues (Tim Reinhold from Clemson) who borrowed the Virginia Tech wind tunnel to test anemometers similar to the one that measured the peak wind speed in Perrine.

Miami Herald July 22, 1993State Attorney General Janet Reno called to check on how strong the winds really were to allay some of the rumors swirling around. The Miami Herald published our wind footprint on the front page in 1993, indicating that the highest winds were north of where originally thought. Our work was finally published as a two-part paper in Weather and Forecasting, which set the stage for objective analysis of hurricane wind fields. Back then the reconnaissance aircraft did not have a way to measure the winds near the surface, so storm intensity was estimated as a fraction of the maximum flight-level winds, resulting in a Category 4 assessment on the Saffir-Simpson scale. After 10 years, analysis of measurements closer to the surface from a new type of instrument, the GPS dropwindsonde, suggested that Andrew may have been a Category 5 storm at landfall. In 2009, research from an even newer instrument (Stepped-Frequency Microwave Radiometer), that remotely senses wind speed from the radiative emission of sea foam, reinforced the Category 5 assessment.

Hurricane Andrew had a profound effect on everyone living in South Florida at the time. It is one of those life milestones from which we measure everything before or after. Miami-Dade County responded with a tough new building code with product testing and enforcement, which influenced the eventual development of a unified Florida Building Code. And it kickstarted the insurance industry into using sophisticated models that could estimate the risk of future Andrews, and performance in emergency management and response was found to influence presidential elections. The rebuilding created an economic boom, but many folks moved away while others moved in transforming rural areas such as Homestead in Miami-Dade, from farm fields into suburbs.

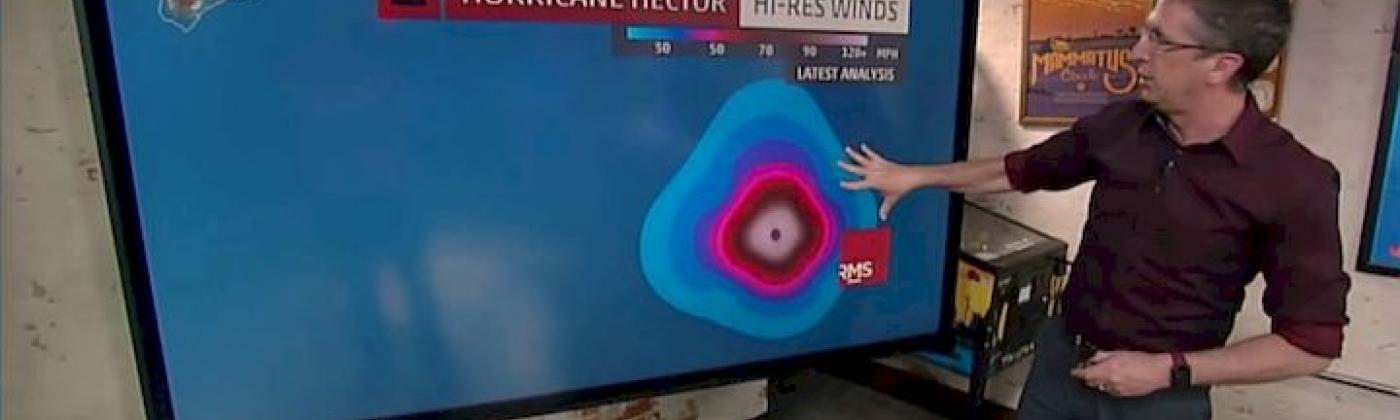

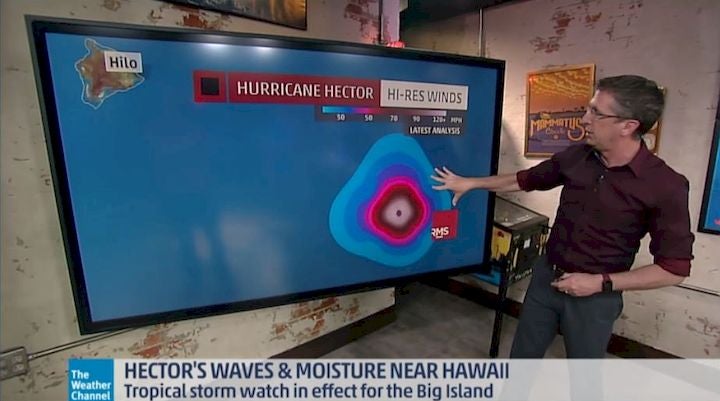

And for me, I went on to develop a research analysis system called H*Wind, now fully within RMS, which now allows us to monitor and analyze the wind field in real time using every piece of data we can get our hands on, such as satellite, dropsondes or portable MET towers placed just ahead of the storm by engineering and atmospheric science students and faculty at the University of Florida and Texas Tech. The HWind fields have become the analysis of record for significant landfall events and a standard for model evaluation with hundreds of citations in peer-reviewed scientific publications.

We work with scientists from all over the world to help develop cutting edge techniques for remote sensing of winds from space, or to provide the best possible forcing for a storm surge or wave model. We have a much better idea of the intensity and extent of the damaging winds now, and also developed new damage scales based on integrated kinetic energy that consider the destructive potential of large storms. RMS HWind is now the world’s leading provider of tropical cyclone wind field data, with observation-based data products for both real-time and historical wind field analyses in the western North Atlantic, Eastern Pacific and Central Pacific basins.

Andrew occurred during a year forecast to have “below normal” activity. I’m often asked, “What kind of year are we going to have”? My answer? It doesn’t matter… just tell me whether Andrew is coming.…